Jean SEGURAContact par e-mail : jean@jeansegura.fr |

|

Avril 1997 JOHN WHITNEY SR: PIONNIER DE L'IMAGE DE SYNTHESE par Jean SEGURA La Cinémathèque Française (République) qui retrace une "Petite histoire de l'abstraction géométrique", avait ouvert un cycle avec des oeuvres d'artistes allemands des années vingt tels Walter Ruttmann, Viking Eggeling, Hans Richter ou Oscar Fishinger. Elle le referme ce vendredi 18 avril (à 19h30) avec la famille Whitney, pionnière du graphisme par ordinateur. Une version plus courte de cette biographie a été publiée dans Libération en avril 1997.

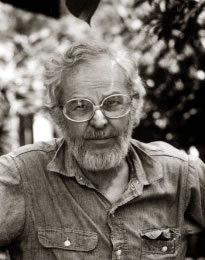

Les belles inventions de ce siècle sont-elles des histoires de frères ? Il y a eu le cinématographe avec Auguste et Louis Lumière et l'aviation propulsée avec Orville et Wilbur Wright. Plus secrète, et plus récente est celle de John et James Whitney qui, dans les années quarante, furent pionniers avant la lettre du graphisme par ordinateur; technique sans laquelle il n'y aurait aujourd'hui ni les dinosaures de Jurassic Park , ni les martiens de Mars Attacks , ni moins encore les innombrables (et souvent invisibles) effets visuels pour le cinéma. Et pourtant, dinosaures et martiens étaient bien loin des préoccupations des Whitney, chantres de la couleur et des compositions abstraites. LA MUSIQUE VISUELLE L'ainé, John (1917-1995), né à Pasadena en Californie est un bricoleur qui passe son adolescence à fabriquer toutes sortes de machines : automobiles, bateaux, planeur et télescope. Également passionné de musique et d'images, il fait ses études au Pomona College où un certain John Cage l'a précédé deux ans auparavant. Puis à Paris où il séjourne de 1938 à 1939 il fait la connaissance de René Liebowitz qu'il fréquente assidûment pendant plusieurs mois. Ce chef d'orchestre alors grand spécialiste d'Arnold Schoenberg enseigne à John les principes des musiques dodécaphonique et sérielle, une période qui marque Whitney pour qui commence à poindre comme il le dit lui-même " l'image idéale d'une peinture fondue dans la musique " chère au compositeur russe Alexandre Scriabine. Ce principe de la "musique visuelle" va guider John Whitney dans le travail de toute une vie: " la composition simultanée de musique mesure par mesure et d'images abstraites ".

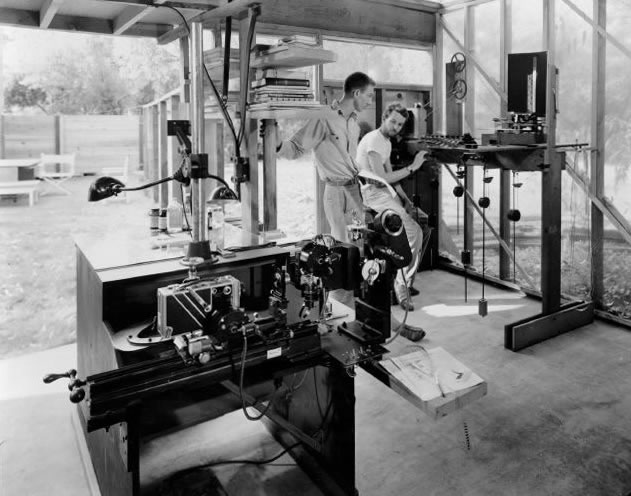

John et James Whitney dans leur studio dans les années 1940. De retour à Pasadena, juste avant guerre, John y rencontre Man Ray et retrouve son frère James (1921-1980). Le cadet des Whitney est artiste lui aussi et revient d'un séjour en Europe où il y a étudié la peinture. Auprès de James, John se remet à construire des machines - pour leur art cette fois-ci - et met au point un système optique d'impression sur film 8 mm permettant de contrôler facilement la fabrication d'images abstraites animées. John et James réalisent ainsi leurs premières séries d'animations muettes à base de cercles et de lignes: Twenty-Four Variations (1940). Puis c'est la guerre pendant laquelle John travaille chez Lookheed Aircraft tandis que James est dessinateur au California Institute of Technology (CalTech). A la même époque, les deux frères transforment une ancienne écurie en studio de prise de vue dans lequel John met au point une imprimante optique pour films 16 mm ainsi qu'un générateur de sons variables à base de pendules qui va rendre possible pour la première fois la combinaison d'une bande musicale aux images. De 1943 à 1944, John et James réalisent avec cet appareillage la série des cinq Films Exercises qui, en 1949, remporteront le premier Prix du Premier Festival de Film Expérimental en Belgique. A partir de 1945 les deux frères poursuivent des voies différentes : James vers la peinture et quant à John, il va bénéficier d'une bourse que la Fondation Guggenhein lui accorde en 1947 et en1948 pour poursuivre son travail sur la composition musicale combinée au graphique. Tout cela se passe bien avant l'arrivée des ordinateurs ! A partir des années 1950 John, qui a emménagé avec sa femme, la peintre Jacqueline Blum, et leurs trois fils à Pacific Palisades (au nord de Los Angeles), exerce toutes sortes de métiers dans le cinéma. C'est pendant cette période qu'il invente le dispositif oil-wipe , textuellement "à essuyage d'huile", afin de créer des images abstraites d'une nouvelle facture. Il réalise avec ce système une dizaine de courts-métrages accompagnés par des musiques de Will Bradley (comme Celery Stalks at Midnight ), Dizzy Gillespie, Sydney Bechet, Mozart ou Anton Karas. En marge de son art, John se met à produire des films publicitaires et commerciaux et fonde sa propre société, Motion Graphics Incorporated. " Le peu d'argent que je gagnais passait principalement à essayer pour moi d'inventer différentes machines " se rappelle-t-il.

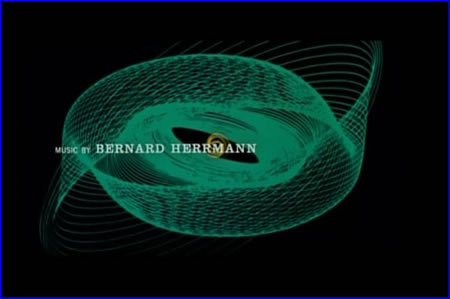

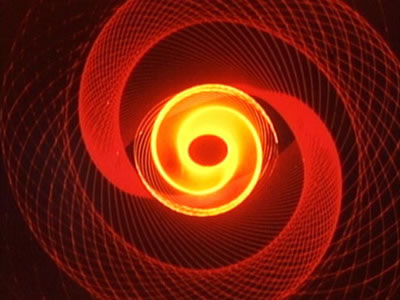

Générique de Sueurs Froides (Vertigo) par Saul Bass. DE "VERTIGO" À "2001" Le génie de John Whitney va donner justement l'une de ses plus belles inventions: en 1957-58 il transforme en appareil de prise de vue un système de visée sol-air ayant servi pour la lutte anti-aérienne pendant la Deuxième Guerre Mondiale et récupéré dans un surplus de l'armée. C'est avec cette mécanique complexe qu'il met au point des procédés d'impression optique de la pellicule à "contrôle de mouvement" ( motion control ) aux noms barbares de "dérive graduelle" ( incremental drift ) et de "balayage de fente" ( slit scan ). L'artiste peut ainsi réaliser des motifs géométriques extrêmement fins et réguliers, fixes ou animés, comme des rosaces ou des canevas dont les formes complexes rappellent les graphes d'un oscilloscope. Premier système permettant de composer des images sur film selon un programme pré-établi, l'ordinateur "analogique" de John Whitney ouvre à la fin des années cinquante une voie inédite dans l'histoire des arts plastiques. Il préfigure aussi, sous une forme primitive, ce que l'on fait avec les ordinateurs graphiques numériques d'aujourd'hui.

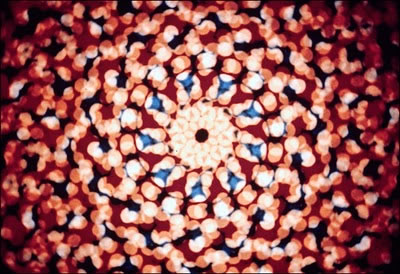

Une des figures du générique de Sueurs Froides d'Alfred Hichcock par Saul Bass. Curieusement, le cinéma grand public sera le premier bénéficiaire de l'invention de Whitney avec le célèbre générique (signé Saul Bass) de Sueurs Froides (Vertigo, 1958). Whitney qui travaillait avec Bass, lui avait déjà fourni nombre de ces images pour des génériques de programmes commerciaux destinés à la télévision, comme celui des automobiles Chrysler. Réalisateur de génériques en vogue à Hollywoood, Saul Bass saura mettre en valeur les motifs géométriques de John Whitney en les associant à l'atmosphère inquiétante du chef-d'oeuvre d'Alfred Hitchcock. La technique "slit-scan" continue d'être exploitée pendant plusieurs années dans de nombreuses productions commerciales ainsi que dans des longs-métrages comme pour le générique de La Blonde défie FBI de Frank Tashlin (The Glass Bottom Boat, 1966). Whitney, qui veut laisser une trace des différentes possibilités de son procédé en réalise un "assortiment" avec Catalog (1961, 7 mn ), un film qu'il ne considère pas comme une oeuvre proprement dite mais plutôt comme une sorte d'inventaire: on y retrouve des rosaces comme celles de Vertigo et bien d'autres formes encore. C'est au cours de cette période que James Whitney réapparaît dans la vie de John pour faire appel, une fois encore, au génie technique de son frère ainé. James qui avait suivi sa propre voie de peintre réalisait lui aussi des films d'abstraction, mais de façon presqu'entièrement manuelle : des cartes avec des milliers de points dessinés la main formant des motifs qu'il filmait au banc titre classique comme dans Yantra (1950-1957, 8 mn). John Whitney se rappelle " Après ce film, je l'ai aidé à construire une machine, similaire à la mienne, sur laquelle il a commencé Lapis ". Grâce au contrôle de mouvement extrêmement fin qu'il obtient sur cette machine, James Whitney réalise avec Lapis (1965, 10 mn) une oeuvre kaléidoscopique très impressionnante inspirée des Mandalas orientaux et accompagnée de musique indienne.

Lapis (1965) une oeuvre kaléidoscopique de James Whitney En marge de ces oeuvres qui ne sont projetées que dans des festivals spécialisés et autres manifestations confidentielles, d'autres images surprenantes issues de l'invention de John Whitney vont frapper le grand public et les cinéphiles avec la séquence d'hallucinations dite "Stargate" du film 2001, Odyssée de l'Espace (2001: A Space Odyssey,1968). Mais contrairement à la légende, Whitney n'a jamais réalisé ces images. Il faut remonter à la période où, au milieu des années soixante, Whitney soustraite alors ses images auprès de Graphic Films, une société d'Hollywood qui réalise des documentaires sur les sondes spatiales pour la NASA. En pleine préparation de son film, Stanley Kubrick, qui connaissait le savoir faire de Graphic Films en matière de simulation visuelle dans l'espace, propose à plusieurs de ses membres de les recruter, notamment Con Pederson, Colin Cantwell et un certain Douglas Trumbull. Pederson, entre temps, réussit à convaincre Whitney avec qui il travaille de lui préparer quelques échantillons d'images composées au « slit-scan » pour les montrer à Kubrick. Puis tout ce petit monde s'embarque pour Londres où 2001 doit être tourné. Whitney, qui a d'autres obligations, n'est pas du voyage. On oublie donc l'artiste, mais pas ses images : Trumbull, génial inventeur (lui aussi) alors à ses débuts, va reprendre le principe du slit-scan pour en élaborer une version plus importante et plus complexe permettant de faire notamment - pour la première fois au cinéma - des images artificielles en 3D. Le résultat est stupéfiant, la séquence une réussite, mais Whitney n'en touchera jamais les dividendes puisque son procédé « slit-scan » n'était breveté qu'aux Etats-Unis. " Car je n'ai jamais eu assez d'argent pour déposer un brevet en Europe " raconte-t-il. Pendant des années et encore aujourd'hui le slit scan (dont on lui reconnaît d'ailleurs officiellement la paternité) va demeurer une des techniques classiques de l'arsenal des effets spéciaux pour le cinéma.

La séquence "Stargate" dans 2011, Odyssée de l'Espace de Stanley Kubrick IBM ET L'ERE NUMERIQUE S'il ne s'est pas intéressé outre mesure au devenir de son invention, c'est aussi qu'entre temps sa carrière avait déjà pris un autre tournant, une opportunité de poursuivre son travail de pionnier. En ce début des années soixante, le graphisme par ordinateur en est encore à ses balbutiements. Un brillant étudiant du MIT, Ivan Sutherland, présente en 1961 sa thèse sur le "Sketchpad", un moyen inédit de faire des dessins directement à même l'écran cathodique, ce grâce aux calculs d'un puissant mais très lourd et coûteux ordinateur. General Motors propose un an plus tard un système comparable, le DAC, dédié à l'industrie automobile et General Electric travaille de son côté sur les premiers simulateurs de vol comportant du graphique temps réel sur écran. Whitney rencontre Sutherland qui, parmi d'autres, lui conseille d'aller voir du côté d'IBM. Et en 1965, grâce à un ami commun, le designer Charles Eames, John Whitney fait la connaissance du tout puissant Président d'IBM, Thomas Watson Junior. Il lui projète son film Catalog tout en lui expliquant qu'il a réussi à obtenir ces images grâce à son seul système mécanique analogique.

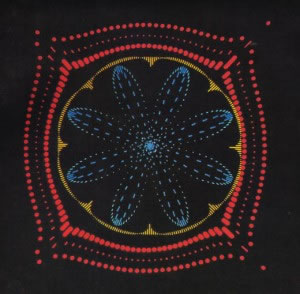

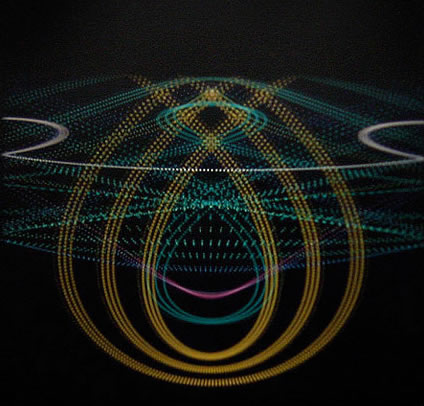

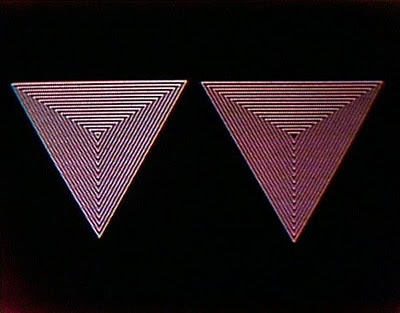

Catalog (1961), film réalisé par John Whitney avec un système mécanique analogique Eames, qui considère Whitney comme un artiste inventif persuade Watson de lui apporter son soutien. À quarante-neuf ans, John Whitney devient ainsi le premier "artiste en résidence" d'IBM. Avec la bourse qui lui est attribuée de 1966 à 1969, il poursuit désormais ses travaux sur ordinateur numérique : un IBM 360 avec une console à tube cathodique IBM 2250. Jack Citron, physicien et chercheur à l'IBM Scientific Center à Los Angeles, intéressé par les applications de l'informatique dans la musique et l'art, écrit pour Whitney un programme (en langages Graf et Fortran). Ce logiciel graphique, qui permet de créer de nombreuses formes géométriques élémentaires (rosaces, cercles, cylindres, hyperboles et autres courbes), est pleinement employé par Whitney pour réaliser Permutations (1968, 8 mn). " Je me suis servi de l'ordinateur comme d'une nouvelle sorte de piano; l'utilisant pour créer une action visuelle périodique, avec l'esprit de révéler un phénomène harmonique (...), une harmonie en mouvement que l'oeil peut percevoir et apprécier " écrit-il. Whitney travaille successivement au West Coast Scientific Center, puis au Health Sciences Computer Facility (UCLA Hospital) " où se trouvaient les plus gros ordinateurs du moment (donnés par IBM), mis à part ceux du Pentagone " se souvient-il. " Je pouvais utiliser ce puissant matériel mais je n'avais pas la priorité, si bien que je travaillais souvent entre minuit et trois heures du matin ". Outre Permutations , Whitney réalise pendant sa période IBM Homage to Rameau (1967, 3 mn) et Experiments in Motion Graphics , un film didactique de 13 mn. À partir des années 1970, il reçoit différentes bourses et autres soutiens et commence à enseigner l'infographie, tout d'abord en 1971 au California Institute of Technology (CalTech), puis de 1975 à 1985 à l'University of California at Los Angeles (UCLA). Il signe la réalisation de films comme Osaka 1-2-3 (1970, 3 mn), Matrix I & II (1971, 6 mn), Matrix III (1972, 11 mn) ou Hexo Demo (1973, 3 mn). Arabesque (1975, 7 mn) qu'il réalise avec Larry Cuba comme programmeur marque un autre tournant technologique puisque les images sont pour la première fois enregistrées à l'aide d'une imprimante électronique, et non plus à l'aide d'une caméra 35 mm.

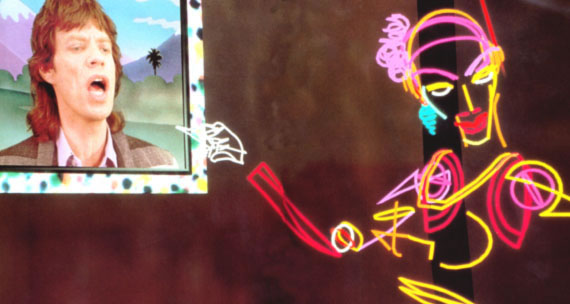

La période numérique : Arabesque (1975) que John Whitney réalise avec Larry Cuba comme programmeur. GÉNÉRATION WHITNEY En 1980, John Whitney publie Digital Harmony , un ouvrage édité par McGraw-Hill, où il relate sa carrière et livre ses réflexions sur les enjeux artistiques de l'infographie. Il faut dire que les années quatre-vingt vont être marquées à la fois par l'explosion de la micro-informatique et par celle de l'image de synthèse dont John Whitney aura été l'un des pionniers. Ses fils reprennent déjà le flambeau : John Whitney Junior (né en 1946) et Michael (1947) font leurs premières armes sur le système analogique de leur père, le premier en réalisant Terminal Self (7 mn), et le deuxième avec Yin Hsien (1975, 8 mn). John Junior, le plus acharné, poursuit le travail de pionnier de son père dans le cinéma : après un court passage dans la société Pictures Design Group où il rencontre Gary Demos, ils rentrent tous deux chez Triple-I où ils restent de 1974 à 1981. Tandis que Triple-I commence à travailler sur le long-métrage Tron , Demos et John Jr fondent en1981 leur propre société, Digital Productions (DP). Les deux associés prennent le risque d'investir 12 millions de dollars dans un super ordinateur, le Cray X-MP, avec pour finalité de faire de l'image de synthèse une véritable activité commerciale. DP réalise ainsi quelques effets spéciaux pour le cinéma comme dans Starfighter (The Last Starfighter, 1984, Nick Castle) ou 2010, l'année du premier contact (2010, 1984, Peter Hyams) dans lequel il fallait simuler la surface de Jupiter; ainsi que le clip musical de Mick Jagger Hard Woman (1985) dont Bill Kroyer réalise la partie 3D. Trop en avance sur son époque, Digital Productions ne parvient pas à survivre économiquement. Après son rachat par la société canadienne Omnibus (qui disparait à son tour), John Junior et Gary lancent en 1987 Whitney Demos Productions en investissant dans un ordinateur de Thinking Machine sans grand succès. Après sa séparation de Gary Demos, John Jr poursuit seul ses activités d'abord dans la société Optomystic ou viennent travailler des infographistes talentueux comme Karl Sims ou Jerry Weil, puis dans US Animation. Michael Whitney devient quant à lui vice-président de Demographics, société fondée par Gary Demos qui passe des contrats de recherche avec des clients comme la NASA, Sony ou Apple. Le plus jeune des trois frères, Mark Whitney (né en 1950), qui est réalisateur est notament l'auteur d'un documentaire sur son père.

Hard Woman (1985), le clip de Mick Jagger produit par Digital Productions fondé par John Whitney Junior et Gary Demos. Car les dernières années de John Whitney Senior ne seront pas celles de l'inactivité. S'il se replie chez lui à Pacific Palisades c'est pour mettre au point avec l'informaticien Jerry Reed un studio de création à base d'ordinateurs personnels PC. Son but est de pouvoir composer simultanément de la musique associée à des images abstraites en temps réel. Il réalise successivement Spirals (1987, 6 mn), puis Moon Drum (1991) une série de douze petits films (édités en vidéocasette) inspirés des imageries sacrées des indiens d'Amériques. John Whitney meurt en 1995, laissant derrière lui une vie fertile d'inventions et de créations, ayant mené jusqu'au bout son rêve de jeunesse de faire vivre le concept de musique visuelle, et, sans l'avoir cherché sans doute, ouvert à toute une génération le monde encore à peine exploré des images par ordinateur.

Jean SEGURA | |

Interview of John Whitney Sr. by Jean SEGURA, journalist, with Carol Shyman, photographer and our one year daughter Viviane Lee Segura-Shyman Saturday, August 7, 1993 - Pacific Palisades, CA.

J.S. Could we begin with the beginning of your career? What is your training, how did you start music or all of this. J.W. Well, you know as a matter of fact, I've just completed an autobiographical documentary, video documentary of myself. My youngest son did the camera work and the directing of it. This was on a commission from Siggraph. It was just completed about the first of this year, and that fills in with a lot of visual material. I could give you a copy, which would give you some kind of background. But the point is that I was in Pomona College a year or two after John Cage. I knew him but at a fairly early time we went in different directions. But at any rate, I did the same thing that he did. After two years of college I quit school and went to Paris to live for a year, just as he had done two or three years ahead of me. And there I was living in a studio that was owned by a concert pianist. I rented a studio from him. My interests, my college interests, were all in music, mostly in music. At that time I met René Liebowitz, who was at that time the master scholar on Schoenberg composing techniques and the only one teaching Schoenberg techniques in Paris. Though I had no formal training with him, my on-going associations throughout that whole year, friendly association with him, exposed me enough to the music of Arnold Schoenberg and the techniques of composing of Arnold Schoenberg that I came back determined to make animated films and compose music - make animated abstract films and compose music. J.S. In which period it was? J.W. This was before the war in 1937 and 38. J.S. And after you came back during the period of the war. J.W. Just before the War when I came back. And then throughout the war time period my brother and I joined ... J.S. Your brother James. J.W. James, yes, joined together and we both started working together in making abstract films. We produced some 5 abstract Film Excercises which are still, in fact, there are two or three film societies right now in Paris that are aquiring prints of those films because they are being shown around to film societies in Europe. You know a Light Cone is one of the groups .... J.S. Which group? J.W. Light Cone is one group and the other is Cinémateque in Paris. J.S. I saw your movie at the Cinemathèque in Paris, yes. J.W. Oh, you did? Well, there's been a sort of revived interest in those films. J.S. I saw this movie Film Excercise and with which techniques are they made? J.W. Well, I'll show you. They were done with very early set of inventions of mine. A pendulum device for composing sound tracks and optical printing procedures for doing the animation. J.S. But not a computer? J.W. No, this was, of course, way before the computers. But having some sort of an innate inherited talent to work with mechanical systems, I found it easy to build my own optical printer and build this pendulum device. J.S. Yes, it's like a clock system. J.W. Yes. So I after the war in the early 50's began to adapt the earliest computer hardware that had been applied to warfare or to fire control devices. These were the first really, really the first stimulus to start developing a computer systems, was all motivated largely by that war. And then after the war, that material, that hardware was readily available for very very little money and I began to adapt some of the earliest mechanical computer systems into an animation system. J.S. Could you explain when exactly did you purchase this system. And how you call it and how did you adapt it? J.W. I began in the late 40's right after the war and ... J.S. 44-45? J.W. 45,46,47. I had Guggenheim fellowship in 1947 and 48. J.S. What do you mean by a Guggenheim? J.W. A Guggenheim is a prestigious foundation in New York and have been giving fellowship grants or funds without any strings attached to people in the creative .... I was one of the first incidentally, next to Maya Deren who was also a filmmaker. I was one of the first to get a Guggenheim fellowship exclusively for filmmaking. And so it was more or less at that time that I was beginning to apply this kind of WWII mechanical computer systems. J.S. How did you call it? J.W. The system that ultimately I adapted and modified strictly for complex animation was a anti-aircraft fire control computer. J.S. What? J.W. Anti-aircraft. It was a computer which was operated ... J.S. On the ground or ...? J.W. From the ground. J.S. On the ground. J.W. On the ground, to look at the approaching bomber planes and direct the whole battery of anti-aircraft guns. J.S. You said, hyper frequency system? J.W. What's that? J.S. That's a hyper frequency beams? Because a radar is a hyper frequency, many Giga-hertz. J.W. This is earlier, before radar and it was just strictly optical sighting systems. But at any rate, be that as it may, ... J.S. That was made by whom? By which company? J.W. It was made by..., I wouldn't be able to say, well yes, there are around New England. (Probably MIT Radiation Laboratory NDLA) There were dozens of small companies that specialized in all this mechanical analog computer technology. And I wouldn't be able to say exactly. J.S. I found in some literature it's M something, M5 M6 J.W.Yeah, that's right, Mark 5, that's right. That was the designation, the military designation of it. Oh you have some information? J.S. Yes, ... J.W. ...about my early work. J.S. Yes, I prepared my interview before, of course. J.W. Mark Five or Mark Four. I don't remember. J.S. M7. It's M7. J.W. Who's this? J.S. That's John Whitney Jr. talking. He said, "When I was 14 my father tried to use a computer for making some images. One day I was going with him in a surplus in LA with the goal to buy an anti-aircraft, made in the 40s, this M7 was made for calculating the position aircraft and enemy aircraft and adjust the shooting. J.W. Right, that's exactly the story. (laughs) J.S. And he said that this machine was the father of computers and resolved the problem by the mechanic process and analogic process. J.W. Right. Right. J.S. The M7 was bought for $250, that's correct, and back at home. J.W. Well, that's the way it was. Out of that I developed both the mechanical techniques of motion control and slit scan, which were the techniques that are very very commonly used in special effects in motion pictures. The 2001 sequence, the "Stargate corridor", is a slit scan. J.S. Well, be talking later about that. J.W. That all began with those mechanical systems. I can show you some more pictures of that. J.S. So, go on. You bought these systems and you started to adapt it to make movies. And then how did you adapt and how the film was printed by the light of this system. J.W. Yes. That's right, well, you would like me to describe how it does that? J.S. Yes. I am interested in that. And which movie did you make with this; what is the first and ... J.W. I did a film titled Catalog which was just an assortment of all of the different kinds of effects that I could do with that. I think they have that as Catalog and they're showing it in France now by this Cinematheque or Light Cone. J.S. Where? J.W. ... I think Light Cone has a print of it. J.S. Where is Light Cone? Is it in Paris? J.W. Yeah. They're in Paris. I've got a catalog and you'll be able to ... I can show that to you. J.S. OK J.W. So throughout the 50's and into the 60's I finally began to do some of that commercially. I did a lot of feature film ... J.S. Did you work with Saul Bass ? J.W. Yes, that's right. J.S. What did you do with Saul Bass ? J.W. Well, the best known was the opening title sequence for... J.S. Vertigo. J.W. Yeah, Vertigo . (laughs) You remember better than I do. J.S. That's the only collaboration with him ? J.W. No. There had been before Vertigo earlier works with commercials and some feature film titles. I had done several major television titles directly, as a direct contractor. The title to the Chrysler show. J.S. Which show? J.W. The Chrysler products show. I don't remember what the name of it .... golly, I can't remember the details about these things. But a lot of television commercial titles. J.S. But what was the techniques that you used? J.W. Using these various slit-scan techniques and I did the title to theThe Glass Bottom Boat (La Blonde défie FBI, 1966, Frank Tashlin with Doris Day, Rod Taylor, NDLA) for example, is strictly slit-scan photography. J.S. Slit-scan and you used your analog systems? J.W. Yes. Using this .. J.S. M7 for doing that, also for doing the Saul Bass' Vertigo title...? J.W. Yes, I was beginning to develop that equipment when I did the various works. In fact, you know it's interesting I realize now that the Vertigo title predated the most advanced perfected form of my mechanical motion control device. In fact, at that point in doing the titling for Vertigo , I had a strictly mechanical, not photographic device, that drew, look there, those kind of patterns (il montre quelque chose sur le mur). Those were doing at the same time by this mechanical drawing machine. That's the scale it was drawing them on. And I did a set of maybe two or three thousand, cells, animation cells, which were taken over to Paramount studios and copied on an ordinary animation stand to do the opening title for Saul Bass's film. J.S. What do you mean by cells? J.W. The animation cells. The punched cell that you ... they have stacks of them. J.S. Cello? J.W. Cello? Yeah. J.S. You did this cello by this technique. J.W. By this .... a version predated the photographic techniques that I finally did. Actually it let to the photographic techniques. I did these and animated these for Saul Bass and for several other commercials. And then I began to think well, why bother to do them onto cells? Why not put a light instead of a pen drawing those lines. Let a light trace that and then have the camera with the shutter open. And so the camera would just see ... you stop and look at it any minute ... one moment you wouldn't understand what it is at all, but the light would be tracing a complete cycle like that and then the camera shutter would shift and then a frame would advance and then it would start doing that same thing over again, and that's how I got into doing the motion control animation. That was the first example of motion control. Because, you see, in this case it wasn't somebody inking and painting animation cells and then taking them to the camera where the camera would photograph one cell at a time. This was a totally integrated system. There was some sort of a mechanical motion going through, all interlocked with the camera. And as soon as it had finished one frame, it would automatically jump ahead and start drawing the next frame. And that's the essence of motion control. And that's what's being used, began to be used in .... motion control is used in all kinds of special effects labs today to run the model of an airplane....like in the Star Wars films they made these models that flew through and then they'd run the model, this time painted blue and put in all kinds of background stuff and then ran the model through the exact same motion with some other parts superimposed in. And that's motion control. That's the essential part of it. And that represents probably a very good example of the earliest form of motion control. J.S. It's made with what? Printer? (Il nous montre des rosaces qui sont dessinés sur un mur qui sont extrêmement régulieres) J.W. Well, they, in this case, it was pouring that pattern as a stream of paint, that one up on the wall over there is still a freer type ... the blue and the green there ... is a pendulum device that poured a stream of paint. J.S. Is that too ... no that was made with analog. J.W. It's a mechanical analog device that ... J.S. We are in the 50's - 60's and you owned your own company? What is the name? J.W. Well, I had Motion Graphics Incorporated was the name at one time. J.S. You make money with all that activity? J.W. A bit of money, a very small amount of money (laughs). I put all of the money I made mostly into trying to invent different machines. Because you see from the very beginning, much as I had to one way or another make a living, I had an absolute passion since my first time in Paris to compose an abstract film that would be an intimate experience akin to that of music. J.S. That's your way, like you, associate, combine music and graphics. J.W. Yes. And so by the mid-sixties I had that film Catalog which I would show as a catalog ... J.S. How long is it? J.W. It's only about 8 or 10 minutes long, but it's just a sequence sampled, it's just like a catalog page after page of new designs and I showed that to ... J.S. It's made when? J.W. It's dated 1961. In the early 60's I showed it to IBM, and I showed it to Charles Eames. And Charles was a good friend of ... J.S. Charles Eames? J.W. Charles Eames was a designer ... well, he designed this chair. And he designed that chair over there and this chair. J.S. How do you spell it? J.W. E-A-M-E-S. As I say, he was a very very successful designer and highly regarded. In New York he was an intimate friend of the President of IBM. I can't think of his name. But at any rate, he actually talked with the President of IBM and told him if you want to spend money in philanthropic support of the arts, you wouldn't want to hire a Michaelangelo to do the Sixtine Chapel. Today, you would give your money to someone like John Whitney. (laughs). And it worked. And I showed then Catalog as a demonstration of just what my mechanical systems would do. With my proposal I wanted funding from IBM to use computers. Because these were, the mechanical systems in that Catalog were mechanical computers; they were not electronic computers. And that was successful. IBM gave me grants from about 1965 right through to 1970. During that time, I began really my pioneering work in computer graphics. So that's where... J.S. How did you adapt your knowledge to the computer? You'd never seen a computer? J.W. Right. It's surprising how perfectly natural it was. You see that kind of a process, though I didn't know it, I could understand getting putting gears together and getting cranks to work like this, you've got a motor turing here and that makes this work, and it gives you an oscillating motion. I could understand all of that, but in fact, within the first year of my research grant, I had a polar coordinate program working on the big IBM monitor. J.S. The Polar ...? J.W. A polar coordinate. Polar geometry. There is Cartesian geometry, which is X and Y and polar is from the center out and then around. And that's exactly what that is. I could draw those as easy as pie on a computer. J.S. You introduced some mathematical functions? J.W. I didn't even get through high school geometry, high school algebra. I did get through geometry. I could understand that better. But and that was a very painful thought because as soon as I started working under this grant from IBM, they gave me access to very very important scientific computer specialists at ... in Los Angeles at the IBM West Coast Scientific Center. And they told me, if you want to do graphics, you have to use mathematics. And that was very painful to hear. But somehow, having done all of this mechanically, I could understand the geometry and understand how it turns into just simply mathematical equations. J.S. What was the interface? Was it just only the keyboard, or did you introduce some programming? J.W. Yes. That's it. J.S. Because at the same period you met or you read something told by Ivan Sutherland who was the inventor of Sketchpad where you can directly interact with the screen. J.W. Right. J.S. With the computer, in fact. And do you use this kind of method. Or it's not .... J.W. Well, I never did, even now, I don't know how to do programming. But I've had the resources of the IBM scientific center. Yes, I met Ivan Sutherland before I started my grant from IBM. And he was the one who said you ought to try IBM. And then Charles Eames helped me to get the ear of, what was his name, Thompson?is that it?, no, I can't remember .. He was the President of IBM, a very very powerful man. J.S. Yes, we can find it. He was the President of IBM in '65? Il s'agit en fait du fils du fondateur d'IBM ( T. J. Watson Sr) : Thomas J. Watson Jr (1914-1993) qui fut dirigeant d'IBM (1952-1979) J.W. In 65. And so he approved my ongoing research grants and so I... J.S. On which machine did you work? J.W. At that time I was using the computer facility at the IBM West Coast Scientific Center and then... J.S. You were still there in the LA area. J.W. Yeah, in the area, Westwood at the University of California Los Angeles. A part : Qu'est que c'est ? je parle un petit peu français, (rires ) But, yes, I used a very large IBM systems. Very soon, I think by 1968, I moved from the West Coast Scientific Center down to the Health Sciences Computer Facility which was in the hospital at UCLA. There at that moment, outside of the Pentagon, that was the largest computer facility in the world. And ... J.S. Oh, yes, in this hospital? J.W. In this hospital, believe it (or not). It was called the Health Sciences Computer Facility, all IBM equipment, and all a gift of IBM. And so it was perfectly natural for them to allow me to use that facility. But I had the lowest priority, so I would go over there to start work there on my projects at midnight and usually I wouldn't get to use the system until 2:30 or 3 in the morning. So all of my film making Permutations... J.S. 2:30 to 3. Only half an hour per day? (Mal compris: en fait il travaillait de minuit à 3h du matin, soit environ trois heures par nuit) J.W. yeah, something like that, in the morning. J.S. At night. J.W. In the dead of night, exactly. And at that time, with that huge computer facility next to the largest in the world, I was drawing the images I was making, it would take 60 seconds to draw one frame on black and white. And I had my own camera, and I would wheel my camera in and I'd focus it on the monitor and I'd hook it up electrically to the computer and the computer would draw one picture and then send the signal to take a picture with the camera. J.S. The camera, a movie camera. J.W. A motion picture camera. J.S. 16? J.W. 35mm. J.S. That's the way you store the frame, the image. J.W. Yeah, right. J.S. Each image was made on the film. J.W. Yeah, on the black and white film, one frame at a time. And that's how I made Permutations. All of those were originally black and white 35 mm sequences and then with an optical printer, my own home-made optical printer, after I filmed the stuff at UCLA I would come back and I had my own optical printer in my studio and I would copy the black and white sequences with a 16 mm camera and color filters and that's how I made permutations in a whole series of films, all the Matrix films and the Arabesque, that entire set of films. J.S. Arabesque was made after or ... ? J.W. Yes, it was made in about 1975. J.S. '75? J.W. Hmmmhm. About the last computer graphic film I made by those procedures. J.S. Arabesque was directly in color, no? J.W. yes, there was the color. Sometimes it was 12 exposures of 12 different runs in the camera to get the colors that were involved in it. It was all by that procedure by copying the original black and white material 35 onto 16 mm color with filters. J.S. That's interesting. And all your movies made at IBM are processed by this method? J.W. Yes. All from 1965 'til 1975 really. And then I .... let's see. J.S. But we cannot do at this period color images? J.W. That's right there was no computer color. And they used to ... very very slow. There was that huge machine and it was only making one frame in 60 seconds ; from 10 to 60 seconds per frame. There was nothing in real time. J.S. It's rapid. It's not so slow. Because after when the image was more and more complicated, we need a lot of time to compute the one frame, for example, the image made by John Jr took 20 minutes or something like that. J.W. Right. But this was never that, ... these kind of images that I was doing were never that complicated. So then that's the end of it. For a period then after 1975 after I had finished Arabesque, I tried and tried to get funding to get my own computer because by that time, there were small computer systems available and I didn't have any success until... and I started teaching at UCLA...until the early 80's, at UCLA I was given a color computer for my class work from a company that made a very very highly specialized color computer, very fast and very beautiful color. And then with students, we took that same original program that I had and got it running on this color computer. But it was still drawing one... J.S. You made this computer? J.W. No, it was a gift from the Chromatics Company which was a very well known computer at that time. J.S. Before continuing with this, I would like to talk about 2001 . 2001 was made before 1968, ... J.W. 68, yeah, 68-69. J.S. And in this period you were at IBM. J.W. IBM right. J.S. And did you work with Doug Trumbull? J.W. That's the strange story. I had up until 1965, I had been doing these commercial things, and one of my clients was a company called Graphic Films in Hollywood. And Graphic Films had been making documentaries for NASA describing and visualizing space probes that would travel in great deep space and landing on the moon. J.S. Space Probes? J.W. Well, the rockets that would take off and travel to the planets. Probe -- it's the name of ... it's a term used by NASA for a missile that is sent off to probe, "to probe" means to ask a question or to explore. J.S. We call that a "sonde". It' s not a sattelite. It's like Voyager? Viking? J.W. Right. Those are space probes. I could've used another word. I didn' think. So they were making documentaries for NASA contracts for these big government NASA contracts to illustrate them so that people could understand what they would be like. So they had developped a very advanced skill in modeling, making models, and imitating the looks of the moon and that's why Stanley Kubrick went to them because they had a world renowned reputation for being able to do these visions of travel in outer space, and at that time I was already doing some special effects for them. I was doing on two or three of the various special films that they did, I contracted, subcontracted, to do a little part of it. And I was developing films in my own studio. And there was a little guy, a teenager, he was in his teams, who would come out from Graphic Films and pick up my film from my lab and take it into the lab and then deliver it to graphic films. He was a "gopher". J.S. Gopher? J.W. Have you ever heard of that? That is a term for someone who goes for something. Someone who drives all around the town. J.S. Go-bet... J.W. Yeah, go-between. And that was Doug Trumbull. (laughs) J.S. Oh yes, really. J.W. yeah. Furthermore ... J.S. At what time? J.W. This was in maybe '6 ..... it could have been in 64, 65, 66. Around several years during that period. So I was still doing some subcontracting for Graphic Films as well as going on with my own filmwork with the IBM grant. So then finally the time came when Con Pederson came to me to say that Stanley Kubrick was making this film in England and would I do some sampes directly to him. So I made some samples using my slit scan technique... J.S. Without a computer. J.W. On my mechanical system. Not on the computer but on my mechanical... J.S. No, but on the analog com... J.W. The analog, that's the word for it , yes. J.S. With the M7. J.W. With the M7, exactly. J.S. And you did some shots ... J.W. I gave it to Con Pederson and this is what I learned next. Stanley Kubrick had hired Con Pederson and Doug Trumbull and two or three other people, Colin Cantwell, who had worked for Lace Noveros. Stanley Kubrick had hired them and had taken them right away from Lace Noveros and Lace Noveros was left out in the cold. J.S. I didn't follow. J.W. Stanley Kubrick had a lot of money, and he saw that, Graphic Films, the company in Hollywood, had all of this know how, so he just hired all of the employees from that company. And he just said come on back to England. J.S. And among them was Doug Trumbull. J.W. Doug Trumbull and Con Pederson and they also took my samples that I had done. I never got paid for any of it. And they just simply... I had my system patented in the United States and I had never been able to spend the money to have them patented in Europe. And they just took it all right to England. They were completely, there was no question of violating any of my patents or any of my stuff. But on the other hand, that's the tough side of the story, but there's another side of the story. Those were the very years that I was working for IBM and that was absolutely ... end of tape, side 1 J.W. So that was the sad part of the story. But the other aspect of it was I was that I was doing what I wanted most to do in my research work from the generous grant from IBM. So if it had worked out that Con Pederson had taken my sample rolls of film to England and said, these are John Whitney's films, hire him, I would have said, no. I don't want to go do that. I am too busy working for IBM. So they just simply they didn't even bother to ask me. They just did it. J.S. Did you appear? Are you present in the title? J.W. No. On the other hand, I have the videodisc done by Voyager, the Voyager videodisc of 2001 and there's a long dissertation on this very part of the story. J.S. What is the Voyager videodisc? J.W. That's the company that makes videodiscs of major feature films. I'll show it to you. My Catalog is in there or at least the roll, the sequences that were used in 2001. J.S. But how the sequence you made on your slit-scan system was integrated in the movie? J.W. Well, it wasn't that. It wasn't anything like that, just the principle and there must be this said for Doug Trumbull. He took those sample reels that I had done there, and he'd seen all of my equipment and saw how it worked. And from there he went on to develop a much more complicated system, which was the true slit-scan system used for the Stargate corridor sequence. He had devised ... J.S. When there are the Jupiter sequence is called the Stargate corridor. J.W. Yes. Right. They have this enormous perspective. This seems to be tearing at you, this abstract thing, and it seems as if you are just moving, and that has been used again and again and again in all of the science fiction films. Because it has a profound visualization of travel in space and at light speed. It really very strongly simulates the effect of light speed. J.S. The slit scan is something going from the top to the bottom of the frame and there is a ... J.W. ...a scanning device. Well, in my case, my system scanned across with the camera mounted this way and it didn't produce very much space. I had a lens, a zoom lens that would zoom back and forth each cycle. You see it has to do this painting it on the film, painting the light, while this action is going on. In theTrumbull setup, he had a camera mounted on a dolly that rolled along for about 17 ft. and the camera would be traveling on, with a short focus lens, traveling on this slit, start with a slit zoomed in so tight, ....the camera so close that the slit would be just out of the frame and then you could imagine if your zoom camera is right, let's take this line, if your camera is just outside this line and you start traveling , now you come back and now the line it comes in, and the line paints and it keeps on coming back and finally the line is right in the very middle of the frame. And all the while, that's been just a slit with hand painted artwork moving progressively behind that slit, so that slit has been painted across the film. J.S. What do you call the slit? It's a line? J.W. The slit, yeah, is a slit, is just a narrow thing with artwork behind it. And it scans across the slit. The slit scans from the outside the frame of the film, right to the center of the frame. J.S. But for one frame.... J.W. Right. It does that once. Now the camera backs up and that's done one one frame, now it has to back up, move the frame ahead, the next frame and then it goes through the whole cycle again. So that takes an enormous amount of time. It takes two or three minutes to truck the camera back for each frame. J.S. For each frame, yes, and we have to change in the color and there are so, there's alot of details and we have to integrate in the frame. This technique is used on a movie for giving the impression, the illusion for torque somebody. J.W. That's a rotary slit-scan. I'll show you, I've got to get an example of that from an Imax film. But it was all my stuff. I invented that technique. J.S. You had the invention and Doug Trumbull used the invention but not your images. J.W. Not my images. I made none of the images. J.S. We have to be precise because sometimes we saw in references like this, John Whitney participate made the, it's your invention used for the movie, that's important. Have you met Doug Trumbull? J.W. Oh, yeah. I've known him all of these years. J.S. Because he's very now involved in special effects in movies and know you know the Back to the Future at Universal is made by him. J.W. Oh, is that so. Yeah, he's I think he's almost completeley out of filmmaking and into doing very special shows, very special entertainment at... J.S. Do you remember his movie Silent Running ? Have you seen that? J.W. Yes, I've seen ... J.S. Yeah, it's a nice movie, an ecological story. J.W. Yeah, right. J.S. OK. I would like to precise the fact on 2001 . Now you were at the period where you finished Arabesque and maybe your grant, now what's happened, oh you are trying to do your own computer. J.W. Yes, I was developing, I was teaching at UCLA and the man who had designed the Chromatics operating system and the whole Chromatics machine left that company and he came out here as a free-lance software specialist. And he came to me and said he was very impressed by what my students had done with the Chromatic machine at UCLA. J.S. What is the Chromatic system? What is the principle? J.W. Well, it's just a very high-powered computer with a very large monitor and enormous resource of color : thousands of choices of color and very high resolution. J.S. And it was the mid-seventies? J.W. In the mid seventies and it was one of the most....it was one of the first and most advanced computer graphics stand-alone computers. It was devoted entirely to doing computer graphics. So when he left that company, he came to me and offered to join with me and develop my animation systems that my students had done at UCLA but only on condition that we did it on a standard machine. So we started developing it on an IBM system. J.S. Which one? J.W. I'm using the 486 now. It was the first IBM 2 or 3 years ago, the 286 I think was the first one. And now that's what I've got here in my studio. And I'll show you what..... Cause now I'm working in full color and in real-time and I'm also composing music and picture all on one system. J.S. And you make still some computer animation? J.W. yeah. J.S. But how....we cannot see them in festivals. J.W. That's it. It happens that right now, the quality of image that I'm getting on a computer monitor is vastly degenerated by putting it onto VHS, the American video system. It's not much better on PAL. And it happens that the way I'm working, it isn't even practical to try to make film, to copy the monitors off film. There's a terrible loss even doing that. So I've got these compositions. I'm beginning to have shows because there are very high-quality projectors. In fact, I think probably these young people that I've been in contact with in Paris, Light Cone, will probably put on a show of my work. I've said you can do it if you can get a good projector. Because you know there are as you've seen at Siggraph, there are projectors that project a full theater-size screen and very high detail and very good... J.S. Beta format? J.W. Yeah, Beta format or yeah that's what, ...Yeah, I'm copying them onto Beta. J.S. Yeah that's the standard now used for showing video and computer graphics, beta SP or something like that. J.W. SP, yeah. J.S Or for TV. Now I would like to ask some parallel questions before and after we can go. Firstly, you work with your brother James. I saw Lapis. It was an amazing and very good movie and what he was doing? And he died when? J.W. '80 or '82. J.S. Oh yes. OK. Just before the explosion... J.W. yeah. Right. J.S. ...of computer graphics. J.W. But he had, though he wasn't as mechanical as I was, he was really a painter, the picture up there is one of his and there are others. I made a new analog computer system and I bought a whole new thing and started all over again. So I gave him my old one. And he used ... J.S. The M7. J.W. He used it to make, ... it was an M4 I think what he had. He took it home to his studio across the mountains here in the valley, and he made Lapis , and after he made Lapis, he didn't want to have anything more to do with it and he went back to his... J.S. That's the only movie he made, Lapis ? J.W. That's the only movie he made with the machines. He's made some very fine films but they were almost all hand-made. They were by hand drawing points and by animating those he used an optical printer and then developing his own film and solarizing the techniques. J.S. And Lapis was made with a mechanical system. J.W. It was really the only mechanical system that he ever used. J.S. Great movie, I like it. J.W. Right. It's a fine one. J.S. And the other question, do you have some relationships with other computer artists at this period? During the 60's, for example, Ken Knolton, Lilian Schwartz, .. J.W. I know them all, but I disagreed with them, and I didn't like what they were doing. I don't know how much they liked what I was doing, but I..., though I knew them and saw them almost all of the time at various conferences and exhibitions of our work. Lilian Schwartz, the only computer things that she did really were with her association with Ken Knolton, and Ken Knolton tried to start doing things himself but he finally realized he didn't have any artistic talent in that sense. He was strictly a scientific man. J.S. A programmer. J.W. Programmer. And I don't think that Lilian has done much else and for example, Stan Vanderbeek worked with Ken Knolton first, but they never, to my way of thinking, they never really approached the probems in a solid way. I'm trying to describe all of that, and I've written an article for , that will be published in the Computer Music Journal next year and that along with my documentary, autobiographical documentary, really brings me up to date from my theoretical point of view. J.S. It's an article under press? J.W. No, it's in draft form. I'll give you a draft of it. J.S. Oh, OK. That's interesting. J.W. But I'd appreciate it if you take whatever you like to quote from it, but I wouldn't like you to show it around too much. It's going to be published in the Computer Music Journal , MIT press. J.S. Another thing. Edward Zajac. Do you know about him, he made supposedly one of the first movies ... J.W. At the ICA in London? That's Charles Surry. I never thought of anything he did, very childish. J.S. What is Ben Laposky? He has an analog system a little bit like yours? J.W. Something like my pendulum device, but well no, as a matter of fact these are oscilloscopes and they're one frame looks handsome but they just go on sort of a blah. They don't grow or show any tempo development. J.S. I don't know that one. J.W. Is that Bridgette Riley? J.S. Michael Noll. J.W. Oh, that's Michael Noll imitating Bridgette Riley. J.S. Herbert Frank J.W. Oh, Herbert Frank, yeah. I think I have this same book. J.S. Where is the Zajac ? Because Zajac is the first movie recorded. J.W. Oh yes , right, Right, Zajac ! J.S. And do you know Vera Molnar in France? J.W. Molnar? J.S. Yeah (lui montrant le livre de Herbert Frank et montrant des images du film de Zajac), this is the first. This first movie in 63 made by on an IBM 7090 and that's the path of the satellite around the earth. Do you know this work? J.W. Yes, I was familiar with all of that. J.S. Yes, I suppose. Did you exchange at this period some work? J.W. I showed my things all along, and they got quite alot of play and the interesting thing is most of these things are museum novelty, yeah. That's how closely .... this was done with my mechanical hand machine and this is done on a scope. J.S. Ah this is on a computer... J.W. IBM yeah. J.S. This other thing is about your son now. When did he start to have an activity in computer graphics? I suppose he was a contributor of Star Trek II , no? J.W. The Michael Crichton film Star Fighter . J.S. Star Fighter? Oh, The Last Star Fighter. Oh yes. J.W. That was quite an advanced use of computer graphics. J.S. Yes. Before Tron ? It was before Tron ? J.W. Oh, no. Tron was before that. And The Last Star Star Fighter (1984) was the first done at Digital Productions. And Tron was done at Triple-I. J.S. Triple I, yes. And, oh yes, ILM made Star Trek II : The Wrath of Kahn. (1982). It seems its before Tron (1982) I read in here. But what is the beginning of John, of your son in computer graphics? J.W. Well, as soon as I had my IBM research grant, John more or less took over my mechanical analog system and made a very nice film on it. And then my son Michael, the next son, also made a film with effects that were done on that mechanical system. And then my youngest son Mark became involved and he's the one who's done the documentary on me now, autobiographical documentary. And he had a very, he's done a very fine film. He had a grant from the Metropolitan and the Getty... J.S. You talk about Mark. J.W. Yeah Mark, a grant of, they did a series of grants for films on art, and Mark got one of those grants. J.S. And now he's doing a film about you. J.W. He did it. J.S. It was already made? J.W. Yes, it's already been made. J.S. And where can we see it? J.W. You'll be able to get a hold of it. Let me see, I could lend you a print if you could mail it back to me. I have a print that I could afford to lend to you. So you can..cause that's much of the stuff that we've talked about. Well, no, some of it's in that documentary. I was starting to say that Mark's with his grant from the Getty and the Metropolitan museum, he did an extraordinarily outstanding film on the last drawings of Leonardo. A year before his death, he did a series of drawings on The Deluge , a childhood experience. That's Mark's film. J.S. Karl Sims did ... J.W. Yes, Karl Sims did the computer animation in there, right. J.S. And what about John? John, he started very early to make some computer graphics. And he used your analog devices? J.W. Yes, give them Light Cone in Paris the'll have his film that he made on my mechanical system after I got my grant and was working on my own work for IBM systems, he did Terminal Self , which is quite an unusually good film too. I like it very much. J.S. Terminal Self? J.W. Yeah. It's his own name. J.S. And after he create his own company? No he worked for ... J.W. He started to work for Triple Information International. J.S. Triple I. He worked for them? J.W. Yeah. J.S. And after he left and he created his own company with Gary Demos. J.W. Yeah, that's right. J.S. Digital Productions. And they bought a Cray. J.W. That's right in Digital Productions. Then they were bought out by a Canadian company that ran their company into the ground in about 3 months, in about 6 months. An unfriendly takeover by this Canadian company. The Canadian company went into bankrupcy in about... J.S. Oh, that's Omnibus? J.W. Yeah. Omnibus. And John and Gary lost out completely. Then they started up their own company Whitney Demos. And that, they lost their financing on that, and that went bankrupt and now John has this US animation. From Whitney Demos they'd given up the Cray. But the had a Thinking Machine, the Karl Sims company, and that's when they hired Karl. And then John took Karl with him to Optimystic which was his company. It's the same company, just has a new name, US Animation. It's no longer Optimystic. But it's his own company and he's not in association with Gary Demos any more. Gary's gone on. Actually, Michael, .. J.S. He created his own company? J.W. That's right. J.S. Demographics. J.W. Demographics. And Michael, my middle son, Michael is Vice President in Demographics at the present time. J.S. And Demographics still exists? J.W. Yes, it still exists. It's not doing very well. J.S. I remember because Gary Demos worked on materials, on the simulation of materials (je voulais dire "fabrics"). I met him in Monte Carlo. He was there in 1988 or 1989 but we didn't meet since this time. J.W. No as a matter of fact, Gary umm. I was at the last year in 1970-71, I was a resident artist at Cal Tech, and Gary Demos was a student there. That's where I first got to know him. That's how he happened to get to know John. J.S. And where is he now? Is he still in LA? J.W. Yeah. J.S. And the company Demographics still exists? J.W. It still exists. It's I say, it's just sort of, it's got NASA and a couple of important contracts. One with Sony, one with Apple and he's been involved in developing the standards for HDTV. So they've been involved in that. But there's more or less pure research. They don't have a, they're not making a product and they don't have a retail clientel or anything like that. J.S. Where were you born and when? J.W. I was born in 1917 in Pasadena, CA. J.S. Thank you very much Fin de l'interview. ...in his laboratory. Avec Carol et Viviane. J.W. Il montre une photo de lui et de son frère : That's Rue Francois Guibert, in the 17th arrondissement. J.S. Ah, yes, in Paris. J.W. It's gone now. I walked around there two or three years ago. (pause for adjustments) So I have this composing capability. These are audio and the drum machine and so I'll play one. J.S. Moon Drum. ...music video demo.... Intervention de Carol Shyman. C.S. Very nice. J.S. Oh, yes. I like it. C.S. This is recent? J.W. Well, it's, I've done a set of 12 of these. They're all based on native American themes of one sort or another. Capturing some what the kind of imagery ambiance of Native American folk arts. J.S. And when did you make that one? J.W. They've been growing. I'd had and published about 12 of them in a video cassette about three years ago, but that was before I had the kind of controls that I have now. And it was published on VHS and there was such a degeneration of the quality of the image that they haven't...that's why I've given up trying. J.S. Je suis sur que Art 3000 ça les interesserait de presenter ca. We work with a French association for art and technology and they are preparing a special event in Paris on computer graphics and I'm sure they would be interested by these movies. And I don't know how we can make something. That's programmed for October or something like that? C.S. The first of October. J.W. Well, I'm showing a set of them at the Long Beach museum and as I say I talked to Pick Chotteroff who's at the Light Cone company, Light Cone association. They have funds from...ah voila, J.S. Ligth Cone, 27 Louis Braye, 75012 Paris Tel: 46 28 11 21. J.W. I think I have copies of that. J.S. Fax 43 46 63 76. J.W. Yes, he gave me several copies. So you can have that. J.S. And they are your distributor for all of your movies? J.W. They are also the Cinematheque and they are distributing some of the stuff now. J.S. And they have Catalog ? J.W. These people have Catalog now. They have John's Terminal Self and they have one copy of my documentary. J.S. The documentary by Mark? J.W. Yeah, the one by Mark. J.S. And what else do they have? And they also have your IBM work? J.W. Yeah, they've got the early works on the 25 Excercises and most of the work. Let me run one more and these are, or we don't have to run it all. J.S. Navajo. ... music video demo ... J.S. Is it 3D image? J.W. Well, there are implications of 3D. J.S. Yes, the data, the part of the data. J.W. Yeah, right. cont. listening to Navajo . J.W. So that's it. C.S. Very good. J.S. Remarkable, yes. I'm very impressed. J.W. S'adressant à Viviane : You've been very good little girl. J.S. Is it possible to have copies of this movie? J.W. Well you see that's the ..., in fact I'm preparing for Long Beach and bringing in Marks SP Beta camera and copy this that way. That seems to be the best way so far we've found to do it. So we'll have an SP Beta and I said to the Light Cone people, if you can get a good barco projector or a very very good quality projector... you see all that's going for this is just the quality for the light and the color and time. And so if I can get it into a theater environment and have a good show, I'm willing. J.S. Do you have some slides, photographies, which can illustrate...we'd like to illustrate an article or something else. J.W. That's where I fall down badly because everybody has such nice beautiful pictures and these take one frame of this stuff and there's nothing there. There is a good illustration... J.S. Il me montre le videodisque 2001 : A Space Odyssey and there is a supplementary section Chapter 38 :Slit techniques. Voyayer I and II Jupiter Flybys. I don't have a player but I will probably buy one one time. J.W. My works are on a laserdisc. These were all the images that were... J.S. (reads) The World of John Whitney, Pioneer of Visual Music laserdisc. Where can I get it? Pioneer special interest and there is Arabesque , Matrix I, Matrix III, a message from Whitney, Permutations and Catalog. Yes, and what is that one? J.W. This is a, they did an English version of this one too. J.S. That is a Japanese version, no? J.W. Japanese, yes. And this was the first one. But on the US edition. It has a lot more pictures. J.S. We can get that in Tower Records for example? J.W. Yes, I think you can. J.S. And the company, the publisher is, Pioneer Special Interest. J.W. Laser Vision. - (J.S.Laser Vision is a techni...) - J.W. Is a disc publisher. Viviane s'est coincée. On arrête. De toute façon c'est fini.

POUR EN SAVOIR PLUS John Whitney, Visionary, un article de David Em, mars 2017 suivi du film An afternoon with John Whitney , réalisé par David et Michele Em en 1991, sur YouTube

|