Jean SEGURAContact par e-mail : jean@jeansegura.fr |

|

Silver Spring (Maryland), 26 décembre 1994 DOUGLAS TRUMBULL : "GÉO TROUVETOUT" DU 7e ART par Jean SEGURA PORTRAIT : DE " 2001 " AU CINÉMA DE L'AN 2000

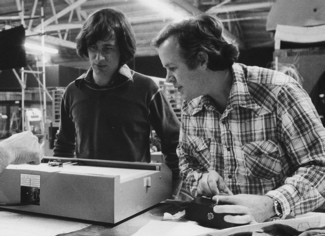

Les jeunes années Les effets spéciaux du film 2001, l'Odyssée de l'espace , c'est lui. L'inventeur du Showscan, c'est aussi lui. Le premier réalisateur de film pour cinéma dynamique, c'est encore lui. Le triptique de salles de cinéma dans l'Hôtel Luxor à Las Vegas, c'est toujours lui. La carrière de cet enfant terrible du cinéma, né à Los Angeles, pleine d'anecdotes et de rebondissements, commence vers le milieu des années 1960. Illustrateur de formation, il rentre dans la société Graphic Films et contribue à la réalisation de films d'animation. Stanley Kubrick qui remarque le travail de cette équipe, va débaucher nombre de ses membres, parmi lesquels Doug Trumbull. pour la préparation de son nouveau film 2001 , l'Odyssée de l'espace.

Séquence, dite Stargate, dans 2001 l'odyssée de l'espace de Stanley Kubrick, 1968 Un grand nombre d'effets spéciaux de ce grand film de SF sont signés Trumbull, notamment la séquence d'hallucinations visuelles lors de l'arrivée sur Jupiter. Il utilisera pour cette séquence une variante de la technique du "slit-scan" inventé par John Whitney Sr, lui-même pionnier de l'image de synthèse. Après 2001, il réalise lui-même en 1971 Silent Running , un film de SF à petit budget. Son savoir-faire en matière d'effets spéciaux appliqués à l'espace lui vaudra d'être appelé dans de prestigieuses réalisations : Rencontres du 3è Type de S. Spielberg (1977), Star Trek : le film ainsi que Blade Runner de Ridley Scott.

Deux passages de Rencontres du 3e Type de Steven Spielberg, 1977 : à gauche l'arrivée du vaisseau mère des extraterestres ; à droite l'aire d'atterrissage au pied de la Devil's Tower dans le Wyoming Mais parallèlement à ces prestations, et après Silent Running , Trumbull va travailler dans le cadre de Future General Corporation, une compagnie de R&D fondée par Paramount pour explorer les différentes techniques cinématographiques hors standard : formats D150, Todao, VistaVision, Technorama, Panavision, etc. Un seul paramètre n'avait, semble-t-il jamais été essayé : la prise de vue et la projection à haute vitesse, supérieure à 24 images/seconde. Trumbull commence alors toute une série de tests qui vont conduire en 1974 à la mise au point du procédé qu'il baptise Showscan : prise de vue et projection à 60 images/s sur pellicule 70 mm, 5 perforations. Les effets sont spectaculaires auprès du public.

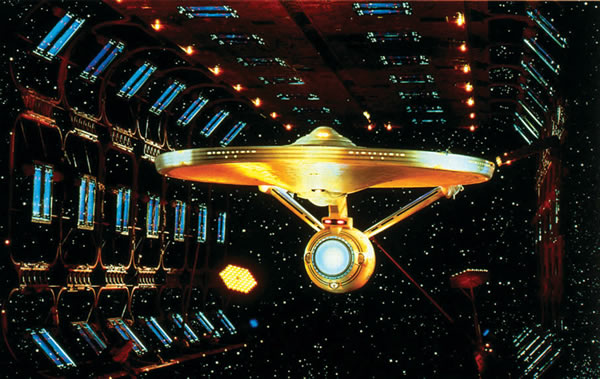

La magie des effets spéciaux signés Doug Trumbull, au service du premier long-métrage issu de la célèbre série télévisée avec Star Trek : le fim de Robert Wise, 1979. En 1974, Trumbull commence aussi à réfléchir sur un procédé de cinéma dynamique en construisant une capsule de simulation avec douze sièges montée sur verrins hydrauliques avec une projection en Showscan, et sur d'autres projets de jeux interactifs. C'est aussi l'année où Spielberg l'appelle pour s'occuper des effets spéciaux de Rencontre du 3e Type, sorti en 1977. Il fait construire à cette époque un grand studio d'effets spéciaux entièrement équipé (matte painting, optical shots, miniatures, etc) dans lequel seront réalisées Rencontre… , puis de Blade Runner et qui deviendra la Boss Film Company. C'est notamment l'apparition des premiers systèmes de prise de vue assistée par rdinateur ("motion control"). Cette technique permettait notamment de pouvoir répéter exactement tous les mouvements de caméras, et donc de faire synchroniser, les prises de vues réelles avec les prises en effets spéciaux sur les maquettes.

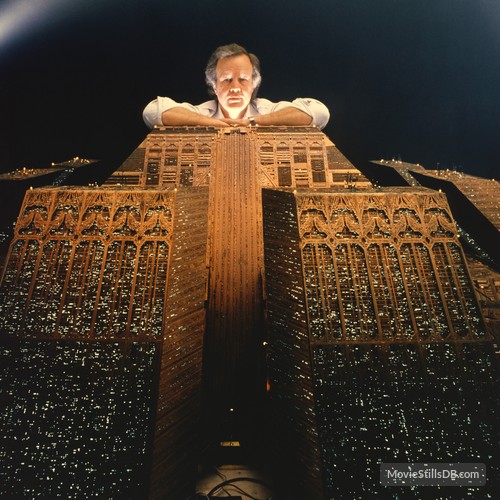

Le décor en maquette de Doug Trumbull dans Blade Runner de Ridley Scott, 1982, et les débuts de la prise de vue en "motion control" Malgré ses réticences, Trumbull est encore sollicité par la Paramount pour réaliser les effets spéciaux de Star Trek , (le Film). Libéré de ses engagements avec la Paramount, Trumbull réalise encore les effets spéciaux de Blade Runner (entre 1980 et 1981 ??). Entre temps il n'a pas abandonné son idée de réaliser un film entièrement en Showscan et propose un projet de long-métrage aux "majors" d'Hollywood : Brainstorm , une histoire de scientifiques qui inventent une machine à enregistrer les pensées. MGM accepte de le produire, mais refuse de prendre le risque financier que représenterait le tournage (et l'exploitation) en Showscan. En 1982-83, Trumbull réalise donc son deuxième, et dernier, long-métrage, avec en vedettes Christopher Walken, Natalie Wood, Louise Fletcher et Cliff Robertson. La mort tragique, le 29 novembre 1981, de Natalie Wood à la fin du tournage fit que Brainstorm manqua de ne jamais être achevé. Après un imbroglio entre la MGM et la compagnie d'assurance LLoyds, le film, terminé, pu sortir aux USA en septembre 1983.

Tour of the Universe : un film en 70 mm, 60 i/s pour la CN Tower à Toronto, 1985. De 1983 à 1987, il se consacre à la compagnie Showscan qu'il vient de créer. C'est là qu'il réalise en 1984 le premier film pour cinéma dynamique Tour of the Universe : un film en 70 mm, 60 i/s qui est toujours en exploitation, pour la CN Tower à Toronto. L'idée sera reprise par Walt Disney avec l'attraction Star Tours à partir de 1987. Mais les désacords de Trumbull avec la politique de Showscan, qui à cette époque souhaite surtout vendre des salles de projections plutôt que produire des films, vont l'amener à vendre les parts de cette société, qu'il avait pourtant contribué à créer. D'une façon générale, déçu par ce qu'il appelle ses "cruelles expériences à Hollywood pendant plus de vingt ans", Douglas Trumbull décide en 1987 de s'installer dans le Massachusetts ... le plus loin possible de Los Angeles !

Silent Running, 1972 et Brainstorm, 1983 : affiches américaines one-sheet pour les deux longs-métrages de science-fiction de Douglas Trumbull

Bruce Dern et ses deux droïdes jardiniers dans Silent Running, 1972

Christopher Walken, Natalie Wood (décédée à la fin du tournage) et Doug Trumbull sur le plateau de Brainstorm, 1983

INTERVIEW : TRADUCTION EN FRANçAIS Jean Segura : On vous connait surtout comme un magicien des effets spéciaux depuis les années 60-70 et aussi comme l'inventeur du procédé Showscan. En 1987 vous vous êtes installé dans le Massachusetts, loin d'Hollywood, pour y faire quoi ? Douglas Trumbull : Au début j'ai créé Berkshire Motion Picture, une société de production avec laquelle j'ai réalisé Back to the Future The Ride en 1990 pour le parc des Studios Universal à Orlando en Floride (voir note 1) . J'ai été très heureux du succès remporté par ce travail, parce qu'il gratifiait une idée que j'avais eu plusieurs années auparavant : celle de constuire ce type de simulateur. Nous avons ensuite édifié une petite salle de projection basée sur le même principe, mais avec un écran beaucoup plus petit, pour pouvoir tester les films tournés dans l'esprit "ride". C'est à cette époque que j'ai eu l'idée de créer une nouvelle compagnie, appelée Ridefilm Theaters. Je croyais pour la première fois possible de fabriquer des attractions de simulation et les implanter dans des endroits comme les centres commerciaux ou les complexes de cinéma multisalles.

Back The Future The Ride dans les parcs à thème Universal, 1991, l'une des premières attractions combinant le cinéma et des sièges dynamiques comme dans les simulateurs de vol. JS : Vous pensiez alors que ce genre de simulateur pourrait gagner le très large marché du diverstissement ? DT : Oui, j'avais l'idée de démarrer une activité qui conduirait à vendre les simulateurs par centaines, voire par milliers. A la même époque, les banquiers avec qui je cherchais à constituer le capital de Ridefilm Theaters firent le rapprochement entre mon projet et la firme canadienne Imax, qui était à vendre depuis deux ans : en combinant Imax avec mon projet, il était possible de lancer Ridefilm, ce qui serait pour Imax l'occasion d'étendre son offre avec de nouveaux produits (voir note 2) . En contre-partie, Ridefilm pourrait profiter de la renommée mondiale de Imax. Aussi nous avons décidé de fusionner. Il y a moins d'un an, Ridefilm Corporation est devenue filiale de Imax et aujourd'hui, je cumule les fonctions de Vice-président de Imax, dont le siège est à Toronto au Canada, avec celles de Président de Ridefilm Corporation, toujours basée dans les Berkshire Hills du Massachusetts.

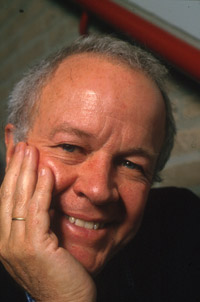

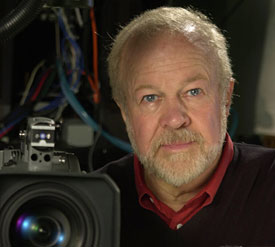

Douglas Trumbull dans les années 2000 JS : Après Back to the Future , vous avez signé la série de "rides" TheSecret of the Luxor Pyramid pour le tout nouvel Hôtel Luxor à Las Vegas. DT : Oui, en fait j'ai réalisé Luxor avant que ma société ( alors The Trumbull Company, fondée en 1992, NDLA ) ne rejoigne Imax. Luxor a été une grande expérience, car c'est à lui seul un petit parc à thème. L'idée repose plus sur celle d'un film à scénario et se distingue donc de ce qu'on à l'habitude de voir dans les rides "classiques" comme les virées en grand huit, les vols-poursuites dans l'espace, etc. Dans Luxor , J'ai voulu introduire des personnages, une action et une histoire à l'intérieur d'un environnement "hi-tech". Trois attractions différentes s'enchainent - dans trois salles de projection différentes - dans un ordre défini comme les trois actes d'un seul récit. JS : Comment ce nouveau genre de cinéma est-il ressenti ? DT : Tout d'abord, c'est un vrai succès commercial. Mais en même temps, nous sommes en train d'expérimenter un concept inédit : celui de "centre de divertissement intégré dans les murs" qui pourra comprendre ultérieurement la réalité virtuelle et divers autres jeux interactifs. Il y a déjà dans l'Hôtel Luxor un espace de jeux d'arcades Sega qui ne désemplit pas. JS : Pour Luxor , vous avez utilisé, semble-t-il pour la première fois, des images de synthèse. Vous aviez pourtant la réputation d'être...... DT : Réfractaire, c'est exact. J'ai vu, à l'époque, tellement de compagnies de Los Angeles se ruiner pour avoir payé du matériel beaucoup trop cher et passé trop de temps à écrire des logiciels. Cela n'avait, à mon avis, aucun sens d'avoir un ordinateur à plusieurs millions de dollars pour faire des clips plublicitaires à la TV ou d'autres choses du même genre. Mais lorsque sont apparus Silicon Graphics, avec ses stations à des prix sensiblement raisonnables, et des logiciels comme Alias, Wavefront et Softimage, alors l'image de synthèse est devenue un vrai domaine d'activité, comme on l'a constaté. JS : Comment s'est organisé votre travail avec la société Kleiser-Walczak Construction pour réaliser Luxor ? Je voulais travailler de façon très rapprochée avec un spécialiste en images de synthèse et recherchais la personne la mieux habilitée pour collaborer sur ce projet. Jeff Kleiser qui a approuvé le projet tel que je lui ai soumis a donc pris la décision de transporter la totalité de son studio ( basé à Hollywood, Californie ) jusque dans le Massachusetts, si bien que nous étions côte à côte dans le même bâtiment pendant toute la production. JS : Comment s'est fait le choix et l'articulation entre les techniques infographiques et les prises de vue réelle ? DT : Nous avons procédé par tests. Cependant, il y a certaines parties où il est préférable de continuer à employer des maquettes, par exemple lorsque la caméra se déplace à l'intérieur d'environnements extrêmement compliqués. En infographie, le facteur limitant est le temps de rendu des images qui peut atteindre quelquefois plusieurs heures. Ainsi pour les séquences les plus détaillées, nous n'aurions pas pu produire plus de huit images par jour, ce qui aurait été beaucoup trop lent. JS : Mais fabriquer et mettre en place des maquettes, cela prend aussi beaucoup de temps ? DT : C'est exact, c'est pourquoi nous n'avons privilégié cette voie que lorsque nous estimions que cela serait beaucoup plus long par ordinateur. En fait nous avons recherché à chaque fois la meilleure solution : "motion control" dans les maquettes, action grandeur nature avec les acteurs, ou infographie ( par exemple, dans le troisième film, les décors sont en maquette, et les objets en mouvement, tels que les vaisseaux, les feux ou les personnages sont en animation 3D, NDLA ) . Et je pense que nous avons fait les bons choix et l'ensemble a été mixé parfaitement puisque nous pouvions utiliser les mêmes bases de données. JS : Depuis la fusion de Ridefilms avec Imax, quels sont vos projets ? DT : Nous avons dû tout d'abord travailler sur toute l'ingéniérie des systèmes hydrauliques, des sièges, des écrans, etc. Nous avons par ailleurs en contrat six films sur la période 1994-1995 que nous pourrons aussitôt proposer à la clientèle des simulateurs Ridefilm. J'ai également organisé les choses pour que le studio accroisse son volume de production en le mettant à la disposition d'autres professionnels. Ainsi, trois longs métrages y étaient en cours de réalisation en 1994 par la société Synergy Productions. C'est la première fois que le "Massachusetts" est à tel point impliqué dans la production de films long métrages d'importance. JS : Et la réalité virtuelle, vous y songez aussi ? DT : Oh oui, beaucoup. Je travaille sur un concept, qu'on pourrait appeler "réalité virtuelle sociale". Pour cela, je ne souhaite pas faire appel aux visiocasques, plutôt dédiés à des expériences individuelles, mais à un dispositif collectif dans lequel cinquante ou cent personnes peuvent participer simultanément : un lieu social, comme un bar ou un restaurant ! C'est juste un projet en cours de développement, mais chez Imax cela fait partie de ce qu'il sera possible d'offrir dans la palette des attractions, notamment dans le cadre de "centres de divertissement intégrés". JS : Serez-vous conduit à utiliser bientôt la vidéo haute-définition plutôt que la bonne vieille pellicule ? DT : Nous avons chez Imax un programme complet de développement sur les écrans larges en vidéo. Parce que nous sentons que le film sera inévitablement remplacé, et que nous voulons être prêts. D'immenses possibilités commerciales se profilent dans l'avenir : non seulement sur les marchés comme les musées et les foires internationales, mais aussi avec celui, encore relativement inédit du "divertissement intégré", pour lequel il existe déjà un public. "Hollywood" qui a voulu trop longtemps ignorer ce marché, devra désormais compter avec des compagnies comme la notre. JEAN SEGURA

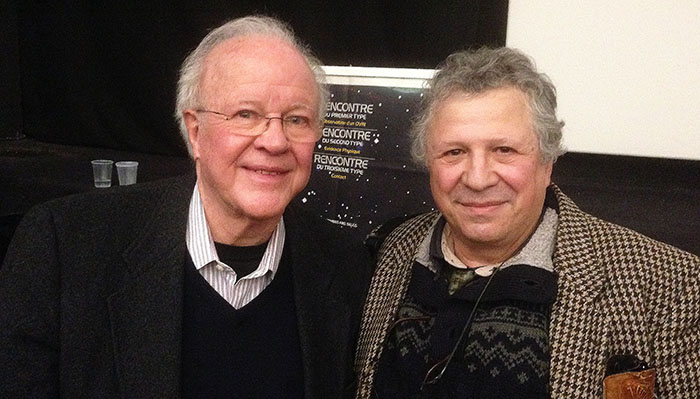

Douglas Trumbull et Jean Segura, le 29 novembre 2016 au cinéma le Grand Action à Paris. LES FORMATS DE LUXOR La composition numérique a été réalisée sur un ordinateur Power Visualization System (PVS) d'IBM, une machine avec 32 processeurs fonctionnant en mode parallèle. Le rendu général des images est de 4000 x 6000 pixels, soit une résolution deux fois plus élevée que pour le film Jurassic Park de Spielberg. Les films sont au format Vistavision (35 mm, 8 perforations, 48 i/s), sauf pour le deuxième épisode qui est en Showscan (70 mm, 5 perforations, 60 i/s). En outre, la séquence des danseurs en 3D du deuxième film, principalement réalisée par Kleiser-Walczak, est projetée en mode stéréo, et des lunettes sont distribuées au public. L'ensemble a été monté en mode virtuel avec le système Avid. J.S.

1. Le tournage est à base de caméra contrôlée par ordinateur (ou "motion control") évoluant à l'intérieur de maquettes, technique favorite de D. Trumbull pour les rides. La projection du film se fait sur un écran Omnimax, et le public est réparti par groupes de six dans des nacelles en forme de voitures montées sur verrins hydrauliques. Inaugurée à Orlando en Floride, la même attraction est aujourd'hui repliquée à Universal Studios Hollywood, en Californie. 2 . Les "rides" étaient jusqu'à présent la chasse gardée des deux sociétés californiennes Iwerks et Showscan et du Britannique Rediffusion Simulation (rachetée en janvier 1994 par Thomson).

3. L'Hôtel Luxor qui appartient à la chaîne d'hôtels Circus Circus Enterprises à Las Vegas a été inauguré en octobre 1993. | |

Interview of Douglas TRUMBULL done by Jean SEGURA, journalist, 15 June 1994 (with Carol SHYMAN, photographer) - TILE 94 - Maastricht, The Netherlands

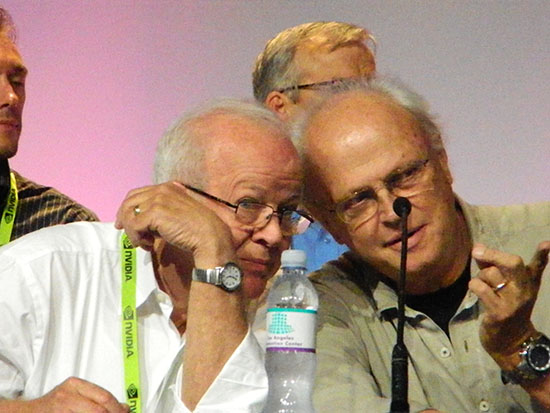

Douglas Trumbull et Dennis Muren d'ILM au Siggraph de Los Angeles, le 8 août 2012. © Jean Segura

J.S. Could you introduce yourself and say your story? D.T. Well, you'll have to ask me a little bit about the story but... J.S. Yeah, of course. D.T. This is Douglas Trumbull, so you'll know my voice. Do you want me to sort of give a little history all the way back to the beginning? J.S. Yes. Maybe when you start with John Whitney or before I don't know. D.T. Well, when I was in school, I was planning to be an architect. J.S. Where were you born? D.T. In Los Angeles. I was born in 1942. And I went to a Junior College in Los Angeles for one year studying architecture but in the process of studying architecture, I took many art courses and I became an illustrator right away. I stopped school and started working as an illustrator. I took my portfolio around to studios trying to find work and I ended up at in small company called Graphic Films in Los Angeles. J.S. In which year it was? D.T. That was probably in 1962 and Graphic Films was working on some very unusual simulation films. Animated films. Simulating the Apollo 11 Landing on the moon. J.S. But with cells. D.T. Right, it was all cell animation. But it was sort of semi-photo realistic. And they also got a contract for a film for the New York World's Fair, that opened in 1964. Which was a special fomat film in 70 mm /10 perf film projected into a Dome-shaped screen. Sort of like Omni-Max. J.S. Before, that was before Omni-Max. D.T. Yes. And it was called the Travel and Transportation Pavillion- sponsored by KLM, Royal Dutch Airlines. It was a film process that was called Cinerama 360. It was the only time that was ever used. And I did a lot of the animated background paintings and illustrations and stars and planets and galaxies, miniature organic material, DNA. It was sort of a "big bang" movie. So that was shown at the New York World's Fair and Stanley Kubric was living in New York at the time and saw the film and subsequently hired Graphic Films to do some preliminary conceptual designs for 2001 , and I was one of the artists working on the conceptual design of 2001 . And then Kubric moved to London to produce the film and didn't continue the contract with Graphic Films because it was just too distant. There was no way to communicate with Graphic Films in Los Angeles to London. I called him up and said, well, can I come and work on the Movie in London. I'll be happy to go. And so he said "yes," sent me a plane ticket and I went to London and I went to the Stanley Kubric film school, because I hadn't done any movies before, really, I hadn't done photography or miniatures or anything like that so I was really just learning on 2001 . I was 23 years old. It turned out I lived there for 2 1/2 years in London working for him on that movie. And that was where I got my training. And it just turned out that I was, I had some unusual blend of skills as an artist and as a technician. My father was an engineer; my mother was an artist and so I'm very comfortable with tools and equipment and engineering problems and that was really what 2001 needed a lot of, unusual solutions to unusual problems. For me working on that movie was just a dream come true, so I got a chance to contribute to many different aspects of that movie. I started out just doing animation, doing all of the read-outs from the Hal computer. And then I got involved in miniatures. And then I got involved in moon terrains and then I started the animation department and then we started doing all of the space backgrounds and stars and Jupiter and compositing shots and I was learning all the way. And then we were nearing, you know, the complicated parts for the end of the film. J.S. The gates. D.T. The star gate. And the production designer on the film, Tony Masters, and other people who were working on the film were trying to figure out what to do. And they were spinning mirrors and lights and smoke and they weren't coming up with anything that worked. And my friend Con Pederson, who was also one of the effects supervisors on the movie had recently been to Los Angeles and was talking to John Whitney and came back and sort of verbally explained to me what John was doing with these moving slits and leaving the camera shutter open and creating multiple exposures in the camera of a sort of accumulated light on the film, and I thought this was... J.S. Regular. D.T. Yeah, just regular 35 mm film ... J.S. No It's regular since the exposure of the movie, of frame by frame, must be regularly exposed by the process. C.S. The regularity. D.T. Yes. J.S. Geometric. D.T. Yeah, it was geometric and as far as I understood, what he was doing was scanning images across the film frame and creating distortions and moving slits and things. And I had never seen those films, I just knew, I got the idea and ... J.S. This proceeding he used with the Vertigo title? You remember the sequence, ... D.T. No, that was something else. J.S. That was something else. D.T. That was just like a pendulum of light creating it. That was just a two dimensional film exposure. But I thought this idea that John Whitney was doing was very interesting. And I sort of understood it verbally and then I tried an experiment on the animation camera in 2001 with a polaroid camera. Everything we shot, we shot polaroids first, to test. And I built a little slit and cranked a piece of artwork through the slit while the polaroid camera moved dimensionally toward the slit to create a dimensional streak rather than a flat streak. So I was trying to take what I thought John Whitney had done two dimensionally and made it three dimensional. That was my idea. J.S. How do you compose 3D with a slit? The slit's in front? D.T. Well, the slit was just a very narrow opening lit from behind and then I had a piece of artwork with colors; the slit was very narrow and the artwork would slide behind the slit. And then the camera would move in and out, so that the slit would become an exposure in space. And I could focus on it automatically. I'll build a focus control device to focus. I just did my first tests with a polaroid camera to show that we could create this dimensional corridor of light and I took a little polaroid down to Stanley Kubric and I said, "I think this would be the solution to this problem. " He said, "looks good." And I said, "well, I'll have to build this big machine. " I said, "I don't know how big it's going to be but it's going to have to be big." And he said, "OK, go ahead and build it." So the engineering side of me started figuring out how to build this thing with very large sheets of glass, about the size of this whole wall of this building. It was a big sheet of glass with artwork and the slit was about a, very very tiny slit like that, about 8 feet long, and the camera on a 30 foot track. So I got help from the Engineering Department at MGM to help me build these things and order special berrings and motors and clutches, differentials, and I figured out how to bolt it all together and make the camera work and designed all of the control systems for it which were based on a series of timers and clocks and motor reversing switches and...

J.S. That was a completely analogic system? There were no digital.... D.T. No No. It was all completely mechanical. It was about as complicated as a washing machine. J.S. Yes, I suppose it was like a clock. Very very, the motion must be very regular very.... D.T. Exactly. I just had little motors that would do incremental motions connected to a darkroom timer. I would just set the dark room timer for 5 sec. and and it would go "bzzzz", you know, and make the motor go a certain distance so every frame would get a different distance depending upon this darkroom timer. And it was quite simple and it had a little box maybe this big with some relays to turn lights on and off and reverse the motors and sequence the camera shutter, things like that. And it worked quite well. That was followed by nine months of photography because it took about a minute to make a frame of film for very long exposures and ... J.S. How long is a sequence? 10 minutes? D.T. I don't know. I never timed it out. Something like that. J.S. It was very different drawing. I remember. It was a very hot spot sequence. D.T. Well, the whole end to the movie, not just that, but the whole end to 2001 had a profound effect on me as a film maker because it made me realise that you could make a very important cinematic event that had nothing to do with dialog, or drama or character development or editing or... . It had nothing to do with the conventions of the cinema. It was a totally different experience. And I thought, "This is very very interesting and this is were I would like to go in my career." J.S. And after 2001 , I remember you did a movie, Silent Running . I saw it. When was it ,in 1972, something like that? D.T. 1971. J.S. That is your script or it's a script ... D.T. Pretty much. I wrote most of it, yeah. Several other writers contributed to it. Mike Cimino worked on the script. Derek Washburn, who wrote Deer Hunter worked on the script. Steve Botchco, who is a big LA writer now, producer of Hill Street Blues and a lot of very successful LA television series, he worked on the script. We all worked on it together. And then I rewrote the whole thing. I don't have screen credit on the whole movie, but I actually wrote most of it. J.S. Did you use special effects, very similar to 2001 ? D.T. No. Extremely simple. I mean, I used things .... J.S. With models? D.T. Very simple models. And front projection. Front projection was used on 2001 in the whole opening sequence with the ape. J.S. A black sheet. What do you call it? D.T. It's called front projection, but it's a 3M retro-reflective material, you know billions of little beads of glass that bounce light back to the camera. And I used that a lot on Silent Running . Silent Running was extremely low budget movie. The whole movie was shot in 32 days. Which is an extremely short period of time for a feature these days. And it included a lot of effects and cost just a little over 1 million dollars. It was just my first film, and it was just a really nice experience. But it wasn't this kind of spectacular 70 mm immersive experience like 2001 . It was a small dramatic film. J.S. How did you move as a special effect director to a creator of a new technology of cinematographe. For me the period between Silent Running and the creation of Showscan, or something else .... D.T. Well, it's sort of a (...) I don't know how to describe it except some people in Hollywood call it "development hell." Have you ever heard that term? J.S. No. D.T. It's when you're (...) , see, after I made Silent Running , I was considered to be a young, hot movie director in Los Angeles. And I had development deals to write scripts and develop feature projects at every studio. I had a deal at Fox, Columbia, Warner Brothers, MGM, all major science fiction movies that I was going to direct. You know I thought, "This is great. My career is taking off. I'm going to be a big success." J.S. And you did how many movies did you participate in? D.T. None. None. C.S. This was the only movie? D.T. Yeah. Silent Running was the only movie. J.S. Yeah, but as as a special effects director. D.T. Well, here's what happened, see, after Silent Running , I was going to direct several films that I was developping at the studios. Every one of these projects ended badly and didn't get produced for all kinds of crazy reasons. I had a wonderful sort of futuristic underwater adventure movie with Arthur Jacobs who had done The Planet of the Apes films, who was the producer of The Planet of the Apes films, very wonderful man. And we were just about ready to shoot and then he died. And so the whole project went into his estate and got tied up by attorneys, and we couldn't make the movie. And then I had a project at MGM which was a wild, futuristic adventure and then Kirk Cucorian decided to build a casino in Los Vegas and closed the studio. So I was there trying to make a movie when MGM decided to go out of the movie business. So that movie didn't get made. Then I had a movie about a futuristic theme park ride at Warner Brothers, and then suddenly all of the management of Warner Brothers changed and they cancelled my project because the new guy didn't want to do the old guy's project, you know, it was the standard Hollywood story. And that's why they call it development hell, cause this happens to many film makers in Hollywood. Cause you can't make a living not making movies. Cause you don't get paid very much during the development phase. You just get a little trickle of money. So I wasn't making a living, and I thought well, you know, I don't feel like I'm doing anything wrong. It's just that all these events that are happening that I can't control. Just trying to make some money, I made a proposal to Paramount pictures that, I said, "I think that there may be some interesting ways to improve the medium itself", because I have a technical side, that's not just my film-making side, I have ideas about cameras, and projectors, and images and technology because I'm familiar with that. So Paramount thought that this was an interesting idea. And we started a research company at Paramount called Future General Corporation. And the specific plan for the company was to take some investment money from Paramount and do some experiments. J.S. When did they create this company? D.T. It was about 1974. About three years after Silent Running . And I started doing a series of film tests of every film process anybody had ever thought of up to that time. You know D150 and TODAO and VistaVision and Technorama and Panavision and Super Panavision and 3D and we rented all of these old cameras and built screens and shot tests and tried exploring what was the history of the cinematic formats. And I thought none of them were very interesting, that there was something missing, it wasn't anything that was worth really going out of your way for. And it wasn't until I had tried all of these formats that I realised that the one thing that we had not tried and that no-one else had tried was to dramatically change the frame rate. So we did a little experiment just in 16 mm film of shooting at 24, 36, 48, 60, and 72 frames per sec and then projecting the film. And that was when we first noticed that increasing the frame rate a lot made a big difference. J.S. The technique existed but only for creating special effects. Because at the projection the frame rate is the same, 24 frames per second. But never used at the frame projection. D.T. Well, what I found out was that there are high-speed cameras for slow motion photography. That was OK. And then I found out that there were high speed projectors used for print screening; there are the laboratories, for high speen print checking so they can save themselves time in the lab by just running the print really fast. And then I found out that this was done by putting a special modification into the Geneva mechanism of the projector so that it would pull the film down during every shutter closure rather than every other shutter closure so you could double the frame rate. It's a very interesting phenomena in film that you can double the projection rate without increasing the speed. It seems crazy. Well, see, there's two shutters in a projector, but the film is pulled down during only one of the shutter closures. Its 24 frame film but it's 48 flickers of light. And the flickers of light is what the Lumier brothers discovered many many years ago to get rid of the flickers. And you remember the movies used to be called the "flicks", cause they flickered badly, until the Lumier brothers figured this out. Thomas Edison, when he was doing his film developments, felt that 50 frames/sec was necessary to achieve motion and get rid of flicker. The Lumier brothers invented the double bladed shutter so everybody was able to reduce the film consumption you know to a 24 frame, it was actually a 16 frames in the early days - the silent movies. In the 16 frame projectors, they had a triple-bladed shutter. So, it would only be 1 frame but it would be click click click, new frame, click click click, you know. So by putting a second pin in the Geneva movements, so that the film would be pulled down in the gate. J.S. Geneva movements? D.T. "Geneva" is the device that pulls the film through the projector gate. J.S. How do you spell it? D.T. G-e-n-e-v-a. Just like the city, the Swiss city. It's a clever device for pulling the film quickly and holding it and then pulling the film quickly and holding it. It's been used in every projector throughout the history of the cinema. And there's a very simple way to modify the Geneva so that it pulls down more often during every time the shutter closes. That gets you to 48 frames/sec. Then you just change the belts and make it go a little faster and it'll go 60 or 72 or whatever. The first Showscan test film I made was at 72 frames/sec. And it was very spectacular. Then I did a test ... J.S. That was made at Paramount? D.T. Future General. J.S. The name of Showscan, did it exist? D.T. Yeah. I gave it that name at the time. And then I did a film test. I shot one scene of just driving down a windy road in a car at 24 frames/sec, 36, 48, 66, and 72 frames/sec. And then I rigged projectors to show the films at those frame rates, and then we set up a laboratory test in a psychological laboratory at a university in California and showed these films to one person at a time, connecting the person to an electroencephalogram with you know brane wave sensors, an electromyogram, which is a muscle sensor to see if they are moving, and heart rate, and respiration, and galvanic skin response, which is like a lie detector test. And we took very detailed graphs of people's response to the movies. And we just proved immediately that as you increase the frame rate, human physiological involvement in the film increases dramatically. Psssew! It's automatic. It just goes, fhhhhew! 60 frames/sec is the maximum, cause if you film or project faster than 60, it doesn't get any better cause your eye can't absorb more than 60, so I settled on 60 frames sec. There was no point in going to 72. There was no further gain. So that became the Showscan process. J.S. It was in which year? D.T. '74. At the same time, I also built a simulator capsule. I built a little theater, 12 seats with a movie screen and a projector mounted on it and the whole thing was mounted on hydraulic rams. J.S. So you used dydraulic hardware? D.T. Yeah. Built at the same time as show scan. These were side by side in the same building. J.S. You used a flight simulator hardware? D.T. No, we actually built a special one. Flight simulators were too expensive, and we had come up with a simpler less expensive way to do the hydraulics. And I also at the same time built an interactive video game with quadraphonic sound and a joy-stick control and a way to take an adventure through a haunted castle, in 1974. J.S. On video? D.T. Yeah. J.S. And how were the images generated? D.T. I had a little tiny camera that moved through a model. The whole system was ... J.S. In real-time? D.T. It was all in real-time, but it was designed to be converted to interactive laster disk. That was our plan. Because laser disc was just being invented at the time. So, I had these three new inventions, and I was making a living. And I showed these inventions to the management of Paramount. Just at the time I got them finished, the management of Paramount changed, and so new management came in. They looked at what I had and they said, "There's no future in any of this. This is no business. We're not interested. We don't want to spend money on it. You're wasting your time. Stop. " So I think that maybe, I was a little ahead of my time. C.S. In '74. D.T. In '74. So Paramount didn't want to put any more money into it and didn't want to develop it, and then Steven Spielberg called and asked if I would (...) actually, I got called prior to that. I got called by George Lucas who wanted to do Star Wars . And I said, "No I'm tired of space movies" and I wanted to do my Showscan thing but when Showscan and the Simulator ride was stopped, Steven Spielberg called and said, "Well, would you be interested in doing the special effects for Close Encounters ?" And I said, "Yeah, OK." C.S. Yeah, different kind of space film. D.T. Different kind of space film. I was really very excited about working with Spielberg because I thought, you know, I'd seen Jaws and I thought, this guy is very interesting. And even though I considered myself to be a director, I'd like to work for this guy. It was a very good decision. I had a really good time working on Close Encounters . And one of the reasons I worked on Close Encounters , because I was under contract to Paramount, they loaned me to Close Encounters . And then I said the deal is that in order to do Close Encounters , I'm going to have to set up some special 70 mm film equipment because we're really going to do really high quality effects in 70 mm. Buy some cameras. Buy an optical printer. Build some motion control systems. We're going to create a special effects studio for this movie. And when the movie is done, I want all of the profits from the movie to go into developping the Showscan process. That was the deal I made with Paramount. So they said OK. J.S. Because, Spielberg was at Universal, no? D.T. Columbia. J.S. Ah, he was at Columbia at this period. D.T. So they agreed to do that. So I had my ulterior motive to continue developping the Showscan process after Close Encounters . J.S. But between Silent Running and Close Encounters , you weren't involved in any movie? D.T. Right. J.S. And Close Encounters was in '76? D.T. It opened I think in '76. I guess we started on it in late '74-'75. Can't remember. So that was a great experience working on that movie and then we got it done. J.S. And Close Encounters was also a new improvement in the special effect technology. And what was the, ... C.S. ...improvement. J.S. Yeah, the improvement. D.T. The important improvement was the development of the really sophisticated motion control system. That was the first, ... J.S. With computers. D.T. With computers and it was the first time we were ever able to record the motion of the camera on location, on a tape, and then bring the recording back to the special effects studio and exactly repeat the movement on miniatures so we can have big panning shots and dolly shots that included flying saucers and the mother ship and things in them. So that was the first time in movie history anybody had ever matched up special effects and live action camera moves. Then I developed the smoke techniques for shooting miniatures in smoke and we developed what we call the cloud tank for creating miniature clouds that built up, you know. So that was a lot of fun. J.S. So that was also the period when ILM started? D.T. Yeah, we were working at the same time. John Dykstra was working at setting up ILM for George Lucas. We were all working at the same time. J.S. Were you in competition? D.T. No. Friendly competition. And some of the same technicians that were building the motion control had built motion control for George Lucas as well. (chew, chew, chew, salt and pepper). So, I finished Close Encounters and Paramount still did not want to do Showscan or Simulator rides, not interested. But Paramount became very, they created a very big problem for themselves with Star Trek , the motion picture. They wanted me to do the special effects for Star Trek and I had refused. And they hired another company which I won't mention who is, who did a terrible job. They spent about 6 million dollars and didn't get any special effects done. J.S. For Star Trek ? D.T. Yeah. C.S. It was not a success at all. D.T. No. J.S. The first one. D.T. Yeah. It was bad, you know, it was a bad story, badly directed, but they were 6 months away from opening the film and they had no special effects. And they had as many special effects shots in Star Trek as Close Encounters and Star Wars combined. There were like 600 shots. It was incredibly ... C.S. To be done in 6 months. D.T. And so nothing was working, and then Paramount came back to me and begged me to do the special effects for Star Trek , and I said, "OK, I'll do it if I can go away. I want out of my contract; I want to take Showscan simulator rides, go away, the minute I finish Star Trek ." And they said, "OK." So that was the way I earned my way out of my contract by doing Star Trek . And I was also developing this Brain Storm movie which was designed to be shot in Showscan. It was going to be the first feature film to be shot in Showscan. And this was asked for by, there was a man named Charlie Bluedorn, a very famous American business man who owned Gulf andWestern company that owned Paramount, a very big conglomerate company, and he had seen a Showscan demonstration that I had put on and told the management of Paramount pictures that they were fools if they didn't make a feature film with this process. And I said, "I agree." And he said, "Well, OK, develop a feature film that can be shot in this process." That was Brain Storm . By the time Star Trek got finished, he died. The management of Paramount didn't want to do the movie in Showscan, so I said, "OK I'm leaving. I'll find someplace else" because I was out of my contract. C.S. At the end of Star Trek you were then finished with your contract at Paramount. You were free. D.T. Right. And I ownded Showscan. So I went all around Hollywood with Brain Storm and Showscan and I said, "Who wants to make Brain Storm and Showscan?" Nobody. Nobody. C.S. To big a risk at the time? D.T. Yeah, but nobody, to this day no one has wanted to take that risk. J.S. But what is the story of Brain Storm ? D.T. It's the story about a man who invents a device that can record your memories. J.S. Oh, yes? D.T. A very unusual movie. And so the only way I could get Brain Storm made as a film was to make it normally, no Showscan. So I did make Brain Storm as a feature film, but not Showscan, and then near the end of production of that film, Natalie Wood died. She was my movie star. So ... J.S. Which actor? D.T. Nathalie Wood. She drowned. The movie production got stopped. I was trying to prove to the movie studio, this was MGM, that I could finish the movie without Nathalie Wood. Because I'd actually shot the movie almost entirely. We were shooting out of continuity. It was very easy to cut the movie together without her. I didn't have to do any fake shots or hand inserts or anything. But MGM didn't have the money to finish the movie and didn't want to finish the movie and tried to claim a 15 million dollar insurance claim from Lloyd's of London. And I was dragged into a deposition under oath to swear, well, could you finish the movie or not. And I said, "yeah, no problem." So Lloyd's of London got in a big fight with MGM. Finally, Lloyd's of London put up the money to finish the movie, which just barely got finished. That was when I decided to leave Hollywood. C.S. Enough Hollywood, really, your negotiations in Hollywood were not very .... D.T. Enough of these guys. I've had nothing but horrible experiences. I just said, you know, I've got to find another way to make a living. C.S. What did you call that, you had a word, development hell? D.T. Development hell, yeah. Well, this was much worse that development hell. This was production hell. So I just felt like I just couldn't trust anybody in Hollywood. Certainly wasn't having a happy experience or a great creative experience, so I decided to move out of Hollywood, move back to Massachusetts, a very beautiful environment, and refocus my energy on simulation rides and non-Hollywood entertainment. It was the only way to be in movies and not have to deal with Hollywood. And that's what I've been doing. J.S. When did you move in Massachusetts? D.T. About 1987. J.S. You also worked on Blade Runner , no? D.T. I did Blade Runner , just before I did Brain Storm . And I built a big special effects studio to do those projects which was the same studio we had done Close Encounters in, and I arranged for my friend Richard Edland to come and run the special effects studio. It's now known as the Boss Film Company in Los Angeles. J.S. And what part of special effects did you do on Blade Runner ? D.T. Everything. Map paintings, optical shots, miniatures, everything. That was really fun. J.S. After you moved to Massachusetts that's the period of your work on the two universe projects. D.T. Right, I did that at Massachusetts. J.S. That was the first piece you did? D.T. Yeah. J.S. What is exactly the Tour of the Universe .? That was the first ride? First commercial ride? D.T. Oh, excuse me, you said, Tour of the Universe ? J.S. Yeah. D.T. That was done at Showscan in Los Angeles before I left. We did that in about 1984 I believe. That was the first commericial simulator ride. And then Disney copied that ride as Star Tours . J.S. Star Tours started in 87. D.T. Something like that. J.S. And Tour of the Universe in 84, in Toronto. D.T. Hmmm. J.S. And Tour of the Universe is in Showscan is it 60 frame/sec? D.T. Yeah. J.S. And it's built with a model, a motion control inside model. D.T. Yeah. J.S. But when you left Showscan, Showscan is now a company independent and ... D.T. Right. So when I moved to Massachusetts, I left Showscan. I sold my stock. See Showscan had decided that they didn't want to be in the film production business either. And I said well, you know, I'm here to make movies, not to sell projectors. So I left Showscan. I'm very proud of Showscan. I think it's a very good film technology. But it really wasn't making much money or being very well managed. J.S. But you are not still involved in Showscan in patents or ... D.T. Well, they owe me a royalty. But I'm not involved in the operation of the company or anything. J.S. But royalties for the patents. D.T. Right. J.S. And when you started in '87, what did you do? In Massachusetts you created a new company? D.T. Started a new company. J.S. Name? What? D.T. Called Birshire Motion Picture. Because we're in the Birkshires of Massachusetts. We were in an old textile mill on a river. In an old, abandoned building. J.S. This company is still existing? No. Birkshire? No? And what, it started in '87 and ...? D.T. That was a company, well, it still exists as a small ride distribution company, operated by my partner. We split up after Back to the Future . J.S. What did you do there when you were at Birkshire? D.T. Well, we did the Back to the Futur ride for Universal. That took about two years. J.S. Back to the Future is a very special combination between Omnimax / (?????) sets, your work and also there is another technology (it's 24 ...?). D.T. 24 frame, yeah. Have you seen the ride? J.S. No, unfortunately. D.T. Oh, you've gotto see it. J.S. We were going to go to Orlando this year. We'll go to the Siggraph and after we'll .... D.T. Maybe I'll see you at Siggraph. I'll be there for that. J.S. Oh, OK. And that's the main work of Birkshire, Back to the Future (ride). Are there other rides? D.T. No. J.S. And after now you are now in Imax. D.T. Yeah. J.S. How did you move from Birkshire to Imax? D.T. I had a very good experience working on the Back to the Future ride at Imax. I was very pleased to have the Back to the Future ride to be such a success because it was a vindication of the idea that I'd had many years before, to build simulation rides. After I did the Back to the Future ride, we built a small theater to test the ride. With one car, one projector and with one small screen. J.S. In Lenox, in Massachusetts. D.T. In Massachusetts. When we were finished, we all realized that this small ride was just as good as the big ride. You didn't have to have an 80 ft screen; the small screen was just fine. And, in fact, it was better in some ways, because we could make the picture brighter because it was smaller, and closer and you could get better focus and better motion and keep centered to the screen. That was when I had this idea to start a new company called Ride Film Theaters. Because this was the first time I felt it was possible to build a simulation entertainment that could fit right into something like this, or in a shopping mall or a multiplex cinema that would have all of the impact .... J.S. It's a very large market. D.T. Yeah, very large market, but it would have all of the excitement of a really giant multimilliondollar theme park ride like Back to the Future , which was a 60 million dollar monster job. So I had this idea to really start a business that could really be very broad and make maybe hundreds, maybe even thousands of simulators. Then the bankers that I was working with to find capital for Ride Film Theaters, we simultaneously found out that Imax was for sale. It's been for sale for about two years. And we realized that by combining Imax and Ride Film, we could really launch this company, it would be a good product for Imax. It would mean that all of the engineering and installation and maintenance and design and filmmaking and equipment would be already done. And so we decided to merge the two companies together. And raise the money to do that. And that's what's brought us to the present day. J.S. When it was merged? D.T. About 6 months ago. And we just went public Friday on the United States stock exchange. J.S. We can purchase some stocks? D.T. Yes. It's called Imax. And we raised ... J.S. New York Stock Exchange? D.T. Nasdac. So we raised about 43 or 44 million dollars. So now we can really go to the next step of really developing the technology of, and even developing the Imax system too. Making better films, installing more theaters. Worldwide sales force selling Ride Film Systems, so it's just a perfect marriage. J.S. But who are involved in this new company? D.T. There's a man named Bradley Wechsler. I can get you all of the information. And his partner, Richard Galfond. They're both New York entrepreneurs. Brad Wechsler is on the Board of Directors of MGM among other things. He's been involved in many different film, Hollwood related entertainment projects. He worked for many years with HBO (Home Box Office) and Rich Galfond is a very ingenious entrepreneur that brings a lot to help the strategy of how to use the money, and how to build the company and how to service our customers better. And I'm the creative guy. J.S. And you are the Vice President of this company, is that correct? D.T. I'm vice chairman. I'm President of Ride Film, but Vice Chairman of Imax. J.S. Ride Film is still existing. D.T. So Ride Film is now a subsidiary of ... end of side one .. J.S. Ride Film is a subsidiary of ...? D.T. Is a subsidiary of Imax. Imax is going to remain in Toronto Canada. Ride Film remains in Massachusetts. J.S. Lenox. I said I would talk about Luxor . D.T. I did like Luxor as a contract from just my own company before I joined with Imax. J.S. Your own company? D.T. Ride Film. Yeah, I started Ride Film before I joined with Imax. J.S. Between Birkshire and Imax, you did another company named Ride Film? D.T. It was called Ride Film Theaters, yeah. J.S. And that was in which year, Ride Films? D.T. This was last year. J.S. Very recent. D.T. Yeah. '93. J.S. Could you talk about Luxor ? It was a very sigular project. D.T. Well, Luxor is a big experiment (laughs) in high technology media entertainment center, and my idea was to have an entertainment center that's like a small high technology indoor theme park. But it's based on film rather than roller coasters or flume rides or anything like that. It's based on the new technologies. And I wanted to try to bring to it some of the entertainment and drama of feature movies. Because theme parks don't have any drama, you know. There's no characters in a flume ride, there's no characters in a roller coaster. There's no story. And I was trying to figure out how to take character development, drama and story and put it into a high-technology, themed environment. And so I had an idea to do three different attractions. But they would all be linked by a common story and common characters. And the three attractions would be the first, second, and third act of one story. J.S. Oh, OK. There is a proceeding. D.S. That's, yeah. And so you should see the attractions in proper order. Which is already a problem because people go there and they see things out of order and they get confused and ... so it's...I'm still working on it. I still want to do some editorial changes and things. The three acts are told in three completely different styles as well. The first act is the simulator ride, the Ride Film simulator. So there are six ride film modules. And it's a very exciting action adventure, sort of Indiana Jones adventure, underground, in a pyramid, using this new technology. It's a very spectacular ride and it's actually superior to Back to the Future . Everybody who's seen Back to the Future and seen Luxor agrees this Ride Film system is better. And then the second act is a Showscan project. I licensed the Showscan process. Have you ever seen Showscan? J.S. Showscan. Yes. D.T. Did you ever see the New Magic film with the guy behind the screen... J.S. No, no. D.T. What have you seen? Have you seen Simulator Rides? J.S. Yeah. In Culver City. Yeah, I went there two years ago. I met (??? Vito de Sato). He showed me a ride. I remember another by ILM... Star Race, something like that. And also at Futurocope I saw something. D.T. Well, I made a demo film at Showscan many years ago. In about 1984, which showed that if you very carefully photographed the film, you could cause the audience to think that what they saw was real. And if you photograph a six foot tall man and project him six feet tall on the screen, and get the perspective and the lighting just right, you could make people believe there's someone in the room. So that's the second act of Luxor is all about that illusion of making you believe there's live performers when it's all film. And it's a very very good illusion. Many many people believe that there's real people there, which is sort of historic in movies. Because people know that movies are movies. They don't believe they're real. But this really fools them. J.S. One of the characters was a body dancing? D.T. That was a 3D part of that. But the characters down on the ..., did you see that show? The characters down on the stage? The TV talkshow? J.S. No. D.T. It's a rear projected 70 millimeter Showscan film, projected into a set, with props and chairs and curtains and plants. You can't tell where the edge of the screen is and it looks like there's people occupying the set and it's a movie, so it works really very well. And that's the second act of this drama. And then the third act is a future special effects adventure. I took like a cinerama screen and put it up vertical, so it curves this way. The seating in the theater is extremely steep. It's about twice as deep as an Omnimax theater. So there's a 4 foot drop between each row of seats. It's a very precarious theater to stand inside of. J.S. That is the real theater you described in Luxor ? D.T. Yeah, I designed the theater. And then we made this very large screen, 70 foot tall vertical format movie. And that movies is a sort of an experiment in trying to tell a complicated story in only 15 minutes. Very fast cuts. Lots of special effects. Very dense movie. J.S. Very dense? D.T. Well, in terms of the amount of information in a short period of time. So that was the Luxor project and I feel like I'm still working on it. I'm trying to get Luxor to agree to let me recut the films and make some more changes. Because I've learned a lot in the process of making these projects about how the audience understands parts of it but they don't understand all of it. It's just too new, too unusual, and so I want to make some changes and it'll make it better. It's very successful and it's making a lot of money and it's sort of an experiment in the beginning of this kind of new indoor urban entertainment center concept, which will ultimately include virtual reality and various kinds of interactive games. There's a big Sega Arcade at Luxor . It's very very successful. J.S. In this kind of project are you paid for all of your work at one time? Or are you interested also in the exploitation ... D.T. I'm interested in the exploitation. I have a piece of the gross revenus at Luxor . J.S. When people pay tickets you have your own share. D.T. yeah. J.S. You work with Jeff Kleiser on this project. I met him. I know him from before, since a long time. It was the first time you used computer graphics because you were very .... D.T. Reluctant. J.S. Yes. D.T. I saw many friends going bankrupt, you know. There were many companies in Los Angeles that went out of business because the hardware was too expensive and the software needed to be written. It didn't exist. J.S. You think about John Whitney Junior. People like that. Gary Demos, .. D.T. Exactly. So it just didn't make any sense to have a multimillion dollar computer trying to do television commercials or something. It didn't work as a business, but when Silicon Graphics came in with really reasonably priced terminals, and you had Alias, Wavefront, and SoftImage, then it became a real business as we all know. And I met Jeff Kleiser. I was looking for what was the right person for working on this project. I wanted to work very closely with the computer graphics person. J.S. Do you think before that we can include computer graphics in the Luxor project? D.T. Oh yeah. J.S In the script? D.T. It was all designed to be done that way. Yeah. And Jeff agreed to do the project. He moved his whole studio to my studio, so we were right together in the same building. And it was because of that that were able to connect the motion control systems, the live action cameras and the CGI all in one common motion system. J.S. You need to use the same database. D.T. Exactly. So we matched that up and it was just great. J.S. The results are successful? D.T. Yeah, VERY, happy with it. J.S. I saw that. D.T. It's incredible. J.S. And how did you choose the elements who can be designed in computer graphics rather than in models? D.T. We did some tests. J.S. For long sequences for example, if we had up to ride in a long way you can use, because models have some limits and also a camera cannot... D.T. Right, and there are certain things that you can still do as models that would take forever to render in CGI. J.S. As what? D.T. Computer Graphics. J.S. yeah, I know, but as what, you said something. D.T. Well, you will see that in this film, there are some sequences where the camera is moving through this extremely complicated environment. But if it was computer graphics, it would take days to render each frame. In some of the most complicated sequences that we were rendering we would get maybe 8 frames rendered in one day. So that was, you know, many hours for one frame. J.S. yeah, but for making models, that takes days too. D.T. Yeah, but there's still certain things that if we had tried what we did with models, with the computer that would have taken much more time. So we tried to find what was the best thing to do with models, what was the best live action, what was the best computer graphics, and I think we made some very good choices. It was very effective. They blended together perfectly. We did all of the compositing digitally on a PVS system. D.T. That's the IBM 32 processor, parallel processor, major powerful computer. And, so that was very successful. We rendered everything at 4000X6000 pixels which is very high resolution. Twice as much as Jurassic Park . 4X as much actually as Jurrasic Park and at 48 frames/sec. So there's twice as many frames to render. And J.S. All of the three theaters are in Showscan? D.T. No. The first ... The Ride Film is a 48 frame Vistavision. Yeah, you know, 8 perf 35 mm at 48 frames. J.S. 35? D.T. 35 mm. J.S. And how many perf? D.T. 8 perf. And then there's a Showscan in the second act. The 3D in the second act is 48 frame, 4 perf 35. And then the third act is again its 48 frame Vistavision. But up on its end. J.S. It's all in 35 mm? D.T. Except the Showscan part, which was 70 mm. J.S. Yeah, and was Showscan in the second one? D.T. Yeah. J.S. 70 mm , 5 perf. D.T. And we did all of our editorial work on an Avid. J.S. Virtual Editing. D.T. Yep. So we used a lot of high technology on this show. And that facility is now being used by three feature motion pictures for a company called Synergy Productions out of Los Angeles, who are in production in London on Judge Dread and two other films, I can't remember what they are. I could find out for you. So now, you know, ... J.S. You are doing some ... D.T. I'm not doing them but the people who are now, I arranged for my studio to be taken over by a group of people, so that we could have more production capability in Massachusetts. So this is the first time Massachusetts has being doing major feature motion picture work. Because we now have all of the equipment, and the talent, and the people to do the world's best. J.S. And what are you doing now? D.T. I'm just doing all my business with Imax, trying to launch the Ride Film Company, which is mostly engineering work to solve all of the hydraulics control systems, seating, and screens, and so we're doing a lot of engineering work and we're contracting six films to be made. Our company is making one of these fims this year. We're contracting two more films out to companies in Los Angeles and San Francisco. We're optically converting the Astroid Adventure film, which is done in Fantasia Land here. J.S. We're going to see tomorrow? D.T. Yeah. Well that's an Imax dome film which we're optically converting to 35 mm Vistavision at 48 frames cause it fits perfectly into a Ride Film system. They're compatible formats. They're both fish eye photography at 48 frames. And we'll produce at least 2 more films next year, so we're able to tell our customers, there's 6 movies right now already committed. So that if they buy a simulator, there's going to be enough movies to run. J.S. For rides, for large theaters? D.T. No, just for rides. J.S. In this movie do you think you will use more and more computer graphics? D.T. I think so. I was just, ... I went to Brussels last night to meet some of the ... J.S. LBO D.T. I went to LBO's facility and I went to Tricks, who are some of the guys who have set up a new company since LBO to do computer graphics. J.S. Oh, they split? D.T. Yeah. J.S. Tricks was the name of the name of the new company? D.T. Yeah. They just did the Cosmic Pinball ride. It's amazing computer graphics. And they rendered that at 60 frames/sec in Showscan, so I'm looking for all of the world's talents because I would like to do some experiments. I'd like to make animated rides, computer graphics rides, live action rides, .... J.S. And virtual reality? D.T. Yeah. J.S. Are you interested in that? D.T. Yes. Very. J.S. What are your plans for VR? D.T. I'm working on what I call, "social virtual reality", which is a group experience virtual reality rather than a one on one experience. J.S. Virtual Adventure for Eyeworks. D.T. In the spirit, yes. Because I don't want to use head mounted displays. I want something that a large group of people can participate in simultaneously, much larger than what they're working on. 50, 100 people at a time. J.S. In a large theater? D.T. Yeah. In a social environment. It's not even a theater. It's really a social enviroment like a bar or a restaurant. So that's just a project in development, but it's part of what we're doing at Imax which is to be able to offer a broader range of different kinds of entertainment, because you need all these varied forms of entertainment to make an indoor entertainment center. J.S. Do you think you must use in the future HD video, like Sony system rather than films? D.T. Well, if you're going to be making a virtual reality system it has to be an electronic display, of course, so it'll be some kind of HD or high resolution graphic display system. And we have a whole program going on at Imax to develop high-resolution large-screen electronic displays. J.S. This is in a program of research at Imax? D.T. Yes, that's right. Because we feel that inevitably, film will be replaced, and when it does, we will be there with the best product. But it's very very high bandwidth. You know, it's a technology that isn't available yet, but we're working on it and so I believe that for our company there's just a tremendous future for the existing business, which is museums and world's fairs. It's a very good business. We now want to add to that the commercial entertainment business, which is a completely different kind of entertainment. You know, it's not educational. So we think there's a very big future for this. I think that high-technology media is now legitimate, profitable business. We just have to deliver it to the public in a reliable and entertaining way, and we'll have a very successful business. And it's interesting that now that the public and the world want this kind of entertainment, Hollywood doesn't know how to do it, because they've ignored it for too long. You know, they could've been first, because I was there in 1974 doing it and they said, "No, there's no future in this." Now it's catch up time, so they need us, so I feel that this is a very exciting time because I'm now associated with Imax which is the largest company with real engineering and real R&D department and the ability for engineers to develop and work very complicated electronic and optical systems. It's a very hard business. J.S. How many people are in Imax? D.T. 300. J.S. Worldwide. D.T. yes. J.S. And the facilities are in ... D.T. Most of them are in Toronto. J.S. And are you coming in France very soon now? Futuroscope? D.T. I'll be at the Futuroscope in September, ISTC. J.S. Is a conference? D.T. Yeah. You should definitely come to that. That's what's called the International Space Theater Consortium. J.S. It's in September. D.T. I think so, yes. J.S. And you're going to launch something special in Futuroscope, no, there are products? D.T. I don't know. I don't know yet. J.S. Like Luxor or ... D.T. Maybe. Don't know yet. J.S. But Luxor can be exported in other places? D.T. Sure. J.S. In Le Caire, for example, I don't know? D.T. Sure.

END OF THE INTERVIEW

Douglas Trumbull dans les années 1990 |